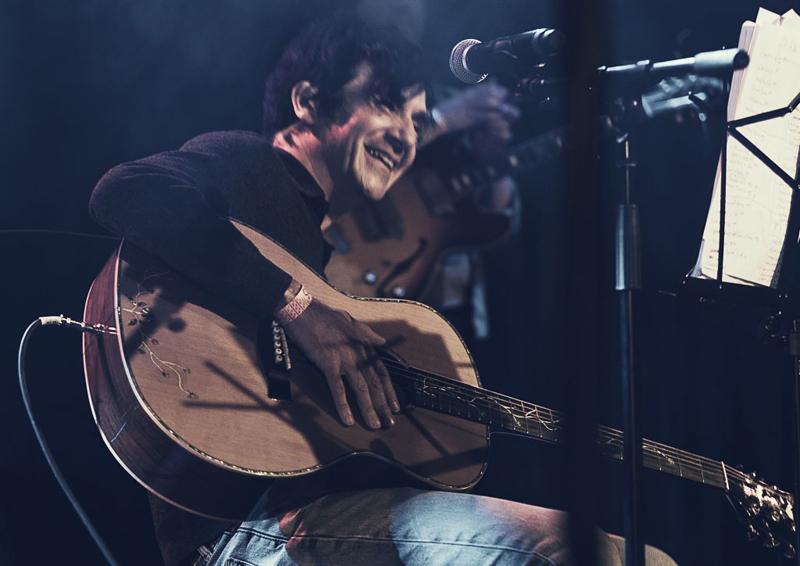

Photograph: © Joakim Bengtsson

Song of myself

“Our essence is ever there in us, seeking expression, release …

If we can be open to ourselves, all manner of experiences arise.

Illumination, direction, song.”

UPON THE CRITICALLY acclaimed publication of his third and fourth solo LPs, Time Waits for No One (February 2021) and Days Go By (May 2021), Cheval Sombre releases a new EP, Althea (November 2021), via Sonic Cathedral, to conclude the singer-songwriter’s tripartite musical triumph.

Featuring beautifully executed covers of Grateful Dead’s “Althea” and Dire Straits’ “So Far Away”, as well as an exquisite reworking of “Are You Ready”, upstate New Yorker, Christopher Porpora collectively draws inspiration from Thomas Merton’s reading of the teachings of Chinese philosopher, Chuang Tzu, with particular emphasis on the meaning of time, the nature of mortality and the essence of love.

Indeed, Cheval Sombre’s contemplative music—a fusion of introspective folk and psychedelia—seeps deep into the soul, rendering it irrevocably altered. Through the understated simplicity of his hushed, raw vocals and elegant open-tuned acoustic guitar, majestically counterpointed by the swelling arrangements of Gillian Rivers’ strings and Sonic Boom’s keyboards, the resultant effect is to be transported into a timeless realm of light and inner sanctuary:

Music doesn’t have to be so ambitious all the time. Once a lovely element is discovered, I say let it ring out for a while—allow the listener to get acquainted with it, to enjoy it, to lean on it. No need to take it away and replace it with all kinds of technical flurry. There is a place in music where we might suggest something eternal, a refuge—something to rely on.

In an updated guest interview for The Culturium, Cheval Sombre gives an intimately compelling account of the inspiration and creative processes behind his three companion pieces and the way in which, when listened in conjunction, an alchemical convergence ensues. Jump to questions specifically pertaining to Time Waits for No One, Days Go By and Althea.

Cheval Sombre, Days Go By, “Well It’s Hard”

PM: You live in the Hudson River Valley region of upstate New York. Could you speak of the effect of being so close to nature, specifically water, and the way in which it infuses your work?

As an aside, I am reminded of another great Chinese philosopher, Lao Tzu, and his seminal tract, the Tao Te Ching, which reveres the element of water, likening a person of great virtue to a flowing river, his profound mind synonymous with its deep water, his benevolent heart with its life-sustaining properties and his sincere words with its perpetual flow.

Cheval Sombre: Living beside the water brings a daily reverence. Each time I step out, gratitude and awe arise, gazing at the river, watching the direction of the waves rippling, a lone barge, passing in slow motion, the sun reflecting in dotted speckles from the north southward. Entire worlds of abundant beauty in just one glance, in each moment. Deer often rest in threes in the grass, curled—and all is silent, except for the wind. This atmosphere has undoubtedly taught me to listen carefully, and to cherish each quiet unfolding, with—what did Anaïs Nin once say?—expectation of miracle.

PM: Do you have a private space to compose your songs and write your poetry? If so, could you describe it to me—objects on the desk, pictures on the surrounding walls, books on the shelf, the outside view from the window?

Cheval Sombre: Much composition has taken place on the go—walking down the street, on restaurant tables, in quiet corners of others’ homes—wherever the work can get done, when it strikes. But I do have a special desk which my father gave to me years ago that I look forward to working on, when I’m not moving through space and time. On it just now are a few drafts of poems that never became very good, notebooks that generous folks have given me over the years still to be filled, envelopes, stamps domestic and international, five candles, a little stained glass lamp, a tiny lava lamp, a stack of blank CDs, a small figure of George (the pig) wearing a crown, a miraculous origami heart made from a dollar bill, some tacked-up notes from dear friends, a note I haven’t noticed in a while that reads precisely, william klein quelques femmes au hasard chapeau + 3 roses 1956, initial sketches I made for the cover art in black ink for these next two Cheval Sombre albums, a photograph a dear one took in a moment of unusual possibility, an old driver’s license of mine which expired, a book of Alan Watts and Merton’s Chuang Tzu translations, an unusual red notebook given to me in Italy filled with scribblings from the Mad Love sessions, a War Sucks pin Pete (Kember) gave to me, a few cowboy album pins from Dean (Wareham), which resemble the two of us riding horses around one another, impossibly sweet drawings my goddaughter made, some extra paper, the pens I like—precious things all. Outside the window, the yard is filled with snow. The hedges which line the street are covered in white, and looking toward the mountain—well I can’t see it today—it’s been snowing for hours.

PM: In Letters to a Young Poet, Rainer Maria Rilke gives advice to an aspiring writer who is seeking guidance at the threshold of his literary career:

There is only one thing you should do. Go into yourself. Find out the reason that commands you to write; see whether it has spread its roots into the very depths of your heart; confess to yourself whether you would have to die if you were forbidden to write. This most of all: ask yourself in the most silent hour of your night: must I write? Dig into yourself for a deep answer.

Would you agree with his words and if so, what has been your own answer to Rilke’s plea?

Cheval Sombre: Ever since I can recall, words (and music) have had a way of visiting me—somehow welling up. I’d be walking down the street feeling as though on the threshold of something, unnamable. An anticipation would lead me—as though I were invested with some wildly potent energy—and it wasn’t until I began to allow myself to try and write that I started to find some direction, some relief, some sense of belonging, purpose, satisfaction—there was a coming home. I didn’t have a Rilke to help guide me in the early days. On the contrary, discovering solace in creation was the result of many feverish hours, stumbling across all kinds of landscapes alone. I didn’t know who to ask about it all—beside prevailing moods, dour as they were, I felt wayward, strange. But in the end, there was nothing I could do except realize these energies. There wasn’t much of a choice, as I recall, and I’m glad for it. Another cannot forbid one’s pure, actual purpose. Purpose simply is. Later, I had a marvellous encounter with Nils-Ole Lund [Danish architect, teacher and collage-artist], who encouraged me to continue, after seeing my notebooks.

Cheval Sombre, Mad Love, “Once I Had a Sweetheart”

PM: Many of your live shows have taken place inside a chapel or sacred space, for example, St Pancras Old Church in London. Could you relate how the architecture of a venue elevates your performance? And how is performing live different from recording in a studio?

Cheval Sombre: I’ve played my fair share of clubs, bars, dives. I spent my first years playing music at The Rhinecliff Hotel, which was just next to the train tracks by the river in a town north of here. The place would rattle when the Amtrak went by, pints of beer spilling across the floor, shards of glass. There was an atmosphere of lawlessness at The Rhinecliff—anything goes, everything permitted—which of course had an effect on the sound, which was then incredibly loud, ramshackle, improvisational. I can’t recall when I began playing churches, though Pete (Sonic Boom) & I have played Union Chapel, St. Giles, St. Pancras (Sonic Cathedral released that performance), and come to think of it St. Marks, too, in New York. I prefer these venues as the music itself is quieter and nuanced these days, meant to be experienced with minimal distraction. It’s been wonderful in England as folks can have drinks if they like while sitting in a pew. In a rock and roll club it’s helpful to be armed with amplifiers and electric guitars, to contend with a bustling crowd. But Cheval Sombre shows are meant to bring an oasis of a kind to folks who wish to step out of the noise, and into something gentle. Sacred spaces cultivate a certain hush, which ends up itself being an integral aspect of the music.

PM: What are the creative influences on your artistic life—music, literature, visual arts, film? And when and why did you decide to make music and poetry your raison d’être?

Cheval Sombre: All kinds of things influence this life—quality of light, scents, atmosphere. For instance, at this moment I’ve a cup of coffee—I’ve added some cinnamon and cacao, which is bringing a loveliness to the morning. Debussy’s Arabesque is playing at a volume, just so. All is influence, so we must choose well. If I were to list music or literary or other artistic sources of wonder, I could fill a (never-ending) book. But to speak about today, I began with a collection of Venetian lute music, I’ve been reading A Drink with Shane MacGowan, if I could be in a room with paintings this evening I’d like them to be Van Gogh’s, and very recently I was glad to have revisited the film My Dinner with Andre. Regarding a raison d’être, I have always had the sense that music and writing chose me—it was something to which I had to awaken.

PM: You have said that you are “obsessed with beauty”. In a similar vein to John Keats’ immortal phrase, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know”, could you expand on this recurrent theme in your poetry and music and why it is so important to you?

Cheval Sombre: This is difficult to distil, as beauty is seen as subjective. But can, for instance, Satie’s Gymnopédies be disputed? All I can say is that when I am in a certain presence, there is a feeling of being at home. And I suppose that seeking the beautiful has always felt vital, especially in the context of a world which often feels so purposefully callous, awful, insensitive. Since I was very small, I had a hunch that while hidden, there was another world to discover in each moment, even if those around me seemed blind to it—and after committing to uncovering such a reality, there it was, and is—what I would call enduring, endless beauty.

Cheval Sombre, Time Waits for No One, “It’s Not Time”

PM: My sense of you is that you are self-effacing and humble. How do you navigate the requirements put upon you to promote your work without sacrificing your inner self?

Cheval Sombre: The only way I can get through it is to keep it about the work, and the work only. In the end, a record (or a book) must speak for itself, as it is an artefact—a world unto itself. When I play a concert, I simply take a breath and do all I can to inhabit the songs fully—or allow them, I might say, to inhabit me. Allowing the work to be the guide has brought me to some fantastic places, physical and otherwise.

PM: Listening to your first ever released record, Cheval Sombre (2008), I am struck by how accomplished it is. Tracks that particularly move me are the alluring “I Sleep” and the magnificent “I Found It Not So”. The harlequin artwork is stunning and seemingly embodies the myriad shades of meaning—longing, personal freedom, regret—that weave their way through the entire piece. Could you expand on that and also tell me the impetus behind your earliest LP?

Cheval Sombre: Thank you for giving it a listen, and bringing it to life. That record holds a dear place in my heart, as it was the first one. It was reissued last year for its 10th anniversary in a luxurious edition, for the first time ever on vinyl. I Sleep and I Found It Not So were two of the very earliest releases, through the incredible Esopus magazine, and Static Caravan, respectively. The artwork grew from some black ink drawings I made, where I envisioned stained glass, based on the paintings of the great Georges Rouault—illustrator Ben Javens realized this perfectly on the sleeve. Grateful that you could perceive “longing, personal freedom, regret” in it—indeed, they are all there.

The first LP came together after Matthew Lyndon Wells [a fellow musician and poet from New York] showed me how to record at home. Soon after, many songs visited. I sent those recordings to Pete Kember (Sonic Boom), as somehow I felt that he alone could understand and embrace this music, and bring too something elegant to complete it. When he contacted me, I remember telling him that I would drink champagne on that very day. This life is often full of disappointments, but it is also filled with magic, and soon we were recording the first LP together in a converted bakery run by the extraordinary Nick Kramer—Dean (Wareham) and Britta (Phillips) played these incredibly subtle, shimmering, sympathetic parts on many of the songs, and then Dean generously offered to release it (Double Feature, 2009). I’ve mentioned this before, but making that record felt much like a long-awaited coming home.

PM: The theme of love appears to be the overarching conceit of your work, sublimely manifested in your next album, Mad Love (2012). Songs that moved me close to tears are “Red Moon”, “Once I Had a Sweetheart” and “February Blues”. In fact, you have mentioned that the cover is a reference to the devastating love letters of Emma Hauck, written to her husband from the University Psychiatric Clinic in Heidelberg, Germany, which are now considered to be works of art.

Being in a state of limerence is a condition we are all familiar with. Indeed, Plato himself likened it to a “divine madness”, whereby someone possessed by eros is afforded a vision of the world not otherwise available to others. Everything seen through the eyes of the lover thus becomes enchanting and sacred. Could you elaborate on this with reference to Mad Love?

Cheval Sombre: Yes—in this state, all is tinged with intensity. Enchantment infuses each moment and even sorrow illuminates, like a flickering fire. There is great elation and utter exhaustion. I agree with Plato there but I would caution too about the treacherous nature of living in such a way. But it isn’t a choice, is it? It happens. I’m still surprised that Mad Love got finished—that it could have been written (and recorded) under the circumstances it was. But there is an extraordinary catalytic power—a seemingly endless reserve of energy—one just burns and burns and burns.

Other experiences of love are just as important, though less manic of course. Sharon Lock (who did the sleeve art) ingeniously introduced the concept of Hauck’s letters, and she could not have been more prescient. On release of Mad Love, folks thought that the songs were written around the story of Emma Hauck, but the album was already recorded before Sharon mentioned this connection. “February Blues” came together at the height of, as you say, much madness. I had heard “Once I Had a Sweetheart” years before on a live album of Joan Baez, and leaned on memory to reconstruct it. “Red Moon” is from a group called The Walkmen—it was one of those rare instances where a song feels as though it is narrating your reality.

Cheval Sombre, Mad Love, “Someplace Else”

PM: On your follow-up remix LP, Madder Love (2014), you play an exquisite adagio for voice and guitar called “Someplace Slow”. It has a purity and innocence to it, which is utterly heartbreaking. How does playing solo feel in contradistinction to collaborating with other musicians, i.e. Pete Kember (Sonic Boom), Darshan Jesrani, Dean Wareham and Britta Phillips (Galaxie 500 and Luna), amongst others?

Cheval Sombre: “Someplace Slow” is a reimagined version of “Someplace Else”, the first song on Mad Love. These incredible artists reworked the song “Couldn’t Do” (from Mad Love) for that release, and I wanted to contribute in my way. My dear friend Matthew Lyndon Wells had recently passed away, and I began singing that song for him on my own, to hold onto him, to sing to him. When I first played the finished version of “Someplace Else” for him long before Mad Love came out, we were in the car, and I could never forget his reaction—it was pure exuberance. I wanted to put something on a record just for him, and I was thrilled that Sonic Cathedral obliged. Playing solo is a vulnerable experience—there is nowhere to run to, nowhere to hide, like Martha & the Vandellas. But it is good to whittle down to the foundation of a song, and explore its essential elements—one discovers what a song is truly made of in this way. And in choosing vulnerability, strength often unexpectedly emerges.

PM: You have just released your latest twin LPs, Time Waits For No One and Days Go By, both nearly a decade in the making. Despite the gap, your songs are still permeated with an elegiac musicality and timelessness that are uniquely your own. From the first album, songs that particularly spoke to me are the majestic “Curtain Grove”, the beguiling title track, “Time Waits For No One” and the instrumental “Dreamsong”, which is one of the most sensual pieces of music I have ever heard.

In your previous guest post on The Culturium, you beautifully outline your creative process for the albums, drawing inspiration from Thomas Merton’s reading of the teachings of Chuang Tzu, in particular, his rendition of a poem, “Autumn Floods”, which speaks of the transience of life: “Time does not stand still” / “Nothing endures” / “All is in movement”. The striking artwork on the album sleeves similarly reflects the fleetingness of time with its gliding white bird gracing both covers, a diamond trail in its wake in a nod of continuity with your debut LP. Could you speak about the paradox of capturing the ephemerality of sound for all eternity?

Cheval Sombre: Initially I wanted to release a double album, but Sonic Cathedral’s wisdom prevailed. The sleeves for Time Waits for No One and Days Go By had to be carefully interrelated, as these records are halves of a whole. The tracklisting of the first was built around the concept of time as linear, sensual, physical, dark, experiential—a birth and death record. The second album approaches time as unmeasurable, lighter—another realm entirely—airier. Something like innocence.

I wanted to do something instrumental, approaching a sort of classical music on these records— “Dreamsong” was recorded in Brooklyn with Darshan Jesrani at his magnificent studio, Bhakti Box. We recorded the guitar first, just before Gillian Rivers and Yuiko Kamakari arrived to play strings. They were both wearing elegant, black dresses, as they came straight from a late-night television performance. I can’t read music, or notate it for that matter, and I ended up whistling the melodies to them—I was astonished at how precisely they both translated the parts—pitch perfect reflections, and Darshan captured it all. I can recall when Pete (Kember) first added his parts to “Time Waits for No One” —he sent a mix and I heard it for the first time driving in the snow and very nearly wept, swerving, so keen was his touch. These moments along the way become somehow very finely etched in one, for all time. Now that the albums are finally being released, I should admit that there has been a tremendous process of letting go.

Speaking of paradox, there are times when one wonders if the work will ever see light of day, and then once all begins moving, a wicked, stubborn reluctance appears. Deep condolences go to Matt Saunders, who mastered Time Waits for No One and Days Go By. He is a perfect gentleman, so I can’t imagine him trumpeting this, but at one point I realized that he was pleading with me to please-just-let-go, let go. I would hear something imperfect in the mix, run it past him, and often he could hear it and tenderly address (bear in mind that these things are minuscule). But as we got closer to delivering the finished work, some of these anomalies would loom terribly for me. I can see now how attachment makes these details horrific, gigantic. Britta (who sings beautifully on “Curtain Grove”) pointed this out to me gently—that letting go of the recordings was bringing these strange instances of resistance. Eventually, I had to yield, as Merton would undoubtedly warn we must.

Cheval Sombre, Time Waits for No One, “California Lament”

PM: Days Go By is a stunning complement to Time Waits For No One. I can truly appreciate the meticulous symmetry you mention regarding their combined content and craftsmanship now that both albums have been released. Songs that deeply resonated with me on the second LP are the elegant “If It’s You”, the scintillating “Are You Ready” and the haunting “Pneumonia Blues”. Many artists change their musical style and focus over the years; however, this is not the case with regard to your own work. Rather, you have refined and deepened your iconic sound through each successive album release, rendering your songs unsurpassed. Could you say a little more about that?

Cheval Sombre: Though subtle, the act of refining is change. About the composition of a singular song, I’ve often asked that if a particular movement works well, why introduce further complexities—for the sake of complexity? As a child I recall sitting in the back of my folks’ car, quietly humming along to a wondrous, perfect moment in a song on the radio only to have it suddenly disappear—and feeling downright bereft.

Thank you for mentioning the songs. The elegance of “If It’s You” is due to Gillian Rivers’ strings—in fact, it is for me the greatest thing that she has ever put down. When I heard that crescendo towards the end for the first time, I utterly lost it. What swells. “Are You Ready” glows like a precious ember, which is a perfect distillation of what happens between me, Pete, and Dean—these three souls make music which sounds like that. Like the haze you see rising along the horizon on an impossibly hot day headed down the highway. Thrilled “Pneumonia Blues” spoke to you. Writing that was an alchemy—a tough situation that yielded an unexpected grace.

PM: You have mentioned that the twin albums bear a similarity with the work of artist and mystic, William Blake. Indeed, the title page of Blake’s illustration of Songs of Innocence and of Experience; Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul depicts a flying bird, which you have echoed, vertically and horizontally, on the sleeves of both LPs. I would like to know why you chose the symbolism of a bird and the meaning behind its respective trajectories.

Firstly, I met Craig Carry when I went over to Cobh, Ireland, to do a Cheval Sombre show. He had done a poster for the performance which he generously hand-numbered and signed for me. The image struck me as it was a bird in an hourglass. A few years later, Craig designed another poster for a gig in Brooklyn. In the package he sent, there was another brilliant, yellow print of an ascending bird—wordless, stunning. The placidity I experienced considering this image was too great to ignore. I knew then that someday I would ask him to be involved with the sleeves.

I began some ink drawings. Time Waits for No One, representative of sensual, linear, worldly time, would feature a bird flying horizontally while the sketch for Days Go By revealed time as vertical, weightless. Both aspects of time felt equally vital and I wanted to honour both. When both records are side by side, an incredible symmetry and merging will happen—an intersection visually, musically and otherwise. In the end, Sonic Cathedral suggested a subtle design touch that perfectly finished the initial vision of these two records, essentially joined.

The cross was always a compelling symbol for me, though I confess I understood very little about its significance. Writing these songs, I began to feel a reconciliation with what had previously felt like disparate aspects of my own life—experience and innocence. Blake of course came to mind. I always saw his work as terribly courageous. To be willing to look at our seemingly paradoxical natures is bold, intrepid. To take a step toward being whole takes an exacting honesty with oneself, which songs can curiously call forth.

PM: Listening to each song whilst simultaneously reading the lyric sheet, I had a revelation of sorts in that both albums appear to explore the theme of *becoming*, be it either pining for lost love—romantic or otherwise—or else craving a deep connection with an elusive “other”. But then, in your penultimate track on Days Go By, “Walking At Night”, which for me is my favourite song of your entire repertoire, you arrive at the end of that journey by the simple act of *being* in the moment, transcending time, space and causation altogether, your beloved finally walking at your side. Would you say that is a fair assessment?

Ages ago, I called my second book of poems, Becoming, in fact. But goodness, though resist we may, aren’t we all ever engaged in this process? Does it ever truly end? Often after working for several years on something, once it comes to a kind of fruition I will attempt to delude myself into thinking my-work-is-finally-done. But is it? Is it ever? Even doing no work is a kind of work. Life continues to happen—to fluctuate and evolve. I can admit that ever since I can recall, there has always been a wild desire to—merge. To experience an overwhelming, transportive harmony. One can live treacherously in this way, craving such bliss, such deliverance from dissonance around each corner.

But music is a relatively safe atmosphere in which to pursue potentially perfect mergings and bliss, elusive harmonies. At one point on “Pneumonia Blues” there is the lyric about wanting to “get on a train / and never come back.” In the studio I attempted to then sing the whistle of a train, a few takes merging with my own voice, for sheer harmony. Oh it’s exhausting—craving perfection(s)—but the pursuit is a riveting journey, often surprising, exotic, fragrant. We find that “perfection” eludes because it is a concept, and with this comes acceptance for what is, and a little peace.

Thank you for mentioning “Walking at Night.” Yes—instead of striving to see the truth, we sometimes are able simply to behold it. The end of thinking. Simply arriving to that place where no work is required, where no words need be spoken—where what is, is embraced. It’s a song about being astonished. About exhilaration.

Cheval Sombre, Days Go By, “Sunlight In My Room”

PM: “Sunlight in My Room” on Days Go By was written for fellow musician and producer, Pete Kember, which you describe as “a flowery lament for a friend who has drifted away. A memory of perfection, of the purity of snow falling once in a moment of perfect togetherness, full of grace—but a heavy acknowledgement of loss, ultimately praising the magnitude of such a connection.”

You have already spoken about how you have had to address the process of letting all your songs go, allowing them to find their own way in the world without you. So I am interested in hearing your thoughts on the nature of renunciation and loss on a larger scale in terms of surrendering everything we cherish and hold dear, given that all things eventually come to pass in the mortal realm—relationships, like your friendships with Pete Kember and Matthew Lyndon Wells; artistic accomplishment; indeed attachment to our very own life and the ultimate sacrifice all human beings must inevitably have to bear.

Cheval Sombre: Illusion can be terribly destructive—the world of what seems rather than what is. Attachment to form can invite devastation. Matt taught me a great deal about this when he died (“He Was My Gang” on Days Go By was written for him). Things resumed between us when I realized that his spirit was indestructible—that indeed it was his spirit which inhabited his body, his spirit which always illuminated.

I wrote “Sunlight in My Room” during a period where illness, geography and other commitments meant that Pete and I hadn’t seen each other in a long while and there was an illusion, a fear, that somehow we could no longer continue our unique, wondrous merging. I didn’t want to let our music go and the song grew from there. Years later, sitting beside him by the sea in Portugal, I silently laughed at myself for imagining that our connection could have ended. It was and it will always be, despite whichever form it takes. Sitting here now, answering your question, I feel much more at ease. Pete is here with me in a sudden breeze, Matt hovers as a cloud. And? All continues.

I certainly, however, have not rid myself of attachment to form. What was that Beatles line? “Because the world is round / it turns me on.” I suspect that renouncing this world to disappear up a mountain would be disingenuous—mostly to myself. There is an element of balance to be practised wherever we find ourselves—no?

PM: You mention that you have written poetry. So far, you have published two collections—In Mine Eyes (2004) and Becoming (2005). “The pull of the world is great”, taken from the first anthology, I found to be particularly profound and lyrical:

After living in a dream

where anonymous

and unseen, stopping

with every rose

and lilac, hanging in

the streets, swooning

in the faintest

breeze, remembering

daisies at the feet

of queens, and gone

from time and place

without leaving

trail or trace or

even petals behind

of flowers now

impossible

to find,

we awake

to find

the pull,

the pull of the

world is great,

it has invaded

our sleep

and caused us

to wake,

and made the dream

to break,

and now memory

litters the street,

and the day now

though golden and sweet

ever remains

somehow incomplete

—Christopher Porpora, In Mine Eyes, “The pull of the world is great”

Could you speak about the difference between composing poetry and writing lyrics? More specifically, the quality of a word when it manifests in harmony with a musical sound as opposed to when it arises from silence?

Cheval Sombre: The nature of how these things arise has always been a mystery to me, and one that I have not tried to grasp—I’ve just been grateful for these occurrences. Long ago, I learned that if I showed up—sitting at the kitchen table before dawn with paper and pen, or finding a quiet place to unlock the guitar—things would happen. With poetry, I developed a strict discipline that led me to sit each day, for years, in the earliest hours. Sometimes words would come, some days nothing was written. I came to understand that each experience was invaluable, whether work was produced or not, as each sitting was connected to the next. One realizes that creation is a continuum, with its own timing.

It’s true that with poems, there is a deliberation over each and every word. Songs generally come to me all at once, often fully formed, and very little editing takes place. The two processes have always remained very separate, discrete. Though there was an unusual cross-pollination with Had Enough Blues (on Time Waits for No One). One evening, the song came to me, and after playing it, I ended up writing a poem about the experience of singing it. You ask an interesting question about what goes on when a word merges with music versus its existence with silence. I have to confess that I do not know—despite the years I’ve been practising both, these alchemies remain mysterious to me. I find these realms impossible to scrutinize—but perhaps the truth is that I prefer not to get too close to the structure of what I would call the miraculous. I don’t want to know too much.

Cheval Sombre, Time Waits for No One, “Curtain Grove”

PM: The German philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer, said: “… aesthetic pleasure in the beautiful consists, to a large extent, in the fact that, when we enter the state of pure contemplation, we are raised for the moment above all willing, above all desires and cares; we are, so to speak, rid of ourselves.”

Do you agree with his statement and if so, what do you believe to be the function of Art—specifically poetry and music—in relation to the opening of the heart and the death of the egoic self?

Cheval Sombre: As I said just before, through working, I’ve come to gladly leave knowledge, as well as the need to know, behind. Stepping into the unknown, one must abandon the accumulated—all that would hinder discovery. One must, in a sense, toss what weighs, what defines, what limits, off the cliff. Sacrifice means making room—we become light, unencumbered, open, able to receive. And when we encounter a great work of art, I do believe that we are delivered from the trappings of the ego, from the petty self. When I am absorbed in certain pieces, there is a taste of eternity, which is beyond all thought, far and free from constructed limitations. We return—we’ve then made the pilgrimage home—at least for some wondrous, prolonged moment.

PM: “I celebrate myself, and sing myself” is the opening line of Walt Whitman’s seminal poem, Song of Myself, a tribute to life, love, time and the unequivocal acceptance of oneself. It occurred to me that this singular declaration of intent could very well be your own.

Cheval Sombre: We cannot be anyone else—can we? We can spend a lifetime trying to emulate others, deceiving ourselves as we go. But fortunately, artifice collapses under the weight of nature. Our essence is ever there in us, seeking expression, release. While we are all undoubtedly connected, our discrete, individual natures—spirits, if you like—lead us, if we make such allowances. If we can be open to ourselves, all manner of experiences arise. Illumination, direction, song. This is not anything we must work at, but rather an invitation to be. To realize what we are can be an arduous road, a difficult process. But ultimately there is relief in being who you are. And why not, from that position—as Whitman advises—sing?

At some point, I found great shelter in realizing that instead of worrying about being someone else, I could quiet down, alone, and let things happen. Words came—a little music from plucking a guitar, tiny black ink drawings. Hours passed with a small set of watercolour pencils. Before long, a world emerges. In the beginning, it is distant but keeping at it brings a clarity. These manifestations, whether merely scribbles, call us to acknowledge this rising within us, which, if we allow without judgement, may reveal an authentic way forward—our own.

PM: Finally, it would appear as if you have arrived at a place where you have perfected your artistry to such a degree, I wonder whether you feel fulfilled creatively at this point? And whither shall you now tread, which path shall you now traverse?

Cheval Sombre: I have often imagined that not another song would ever come—that the mysterious source was somehow exhausted. And then? In some later moment I pick up a guitar, just to strum, and a world unfolds. If any plan exists, I suppose it is simply to allow what is blossoming, to blossom.

Cheval Sombre, Althea, “Althea”

PM: It would appear that, since we last spoke, many good things have blossomed for you musically—the release of a new three-track EP, Althea—so it would be nice to reconnect with you and learn how your life is unfolding for you right now.

Cheval Sombre: This will be it for a while—musically. This EP is the third and final element of Time Waits for No One and Days Go By—all released in one year, all joined. The sleeves (beautifully executed) by Craig Carry reveal this connectedness when all three releases are seen side by side. 2021 was a bit of a whirlwind. Nat of Sonic Cathedral mentioned that we’d doubled the entire discography in just one year.

PM: “Althea” is the beautifully haunting cover version of the Grateful Dead’s masterpiece. On one level, this ornate song appears to be about the vicissitudes of a volatile love affair. But listening a little deeper, myriad layers of meaning start to unfurl—frustration with life, mental anguish, the nature of death. Indeed, Hamlet’s soliloquy is even referenced, “Sleeping and perchance to dream”, being Shakespeare’s evocative meditation on the relative merits of whether or not life is worth living.

And thus, the singer pours out his angst-laden heart to the only one that will listen, Althea, who is more than ready to dispense the divine inspiration he seeks, the salvific love he needs. In fact, Althea may even be mythical Alathea herself, the Greek goddess of Truth and the personification of the sacred feminine. So could you elucidate your reasons for rendering your own musical offering of the Grateful Dead’s single, as well as the way in which its lyrics resonate with your own life?

Cheval Sombre: I heard “Althea” on the radio, en route to the hospital, where my father was very seriously ill. Somehow, I had never heard it before—I had seen the Dead a few times when I was younger and had always admired their work—but as the song unfolded, I was just stupefied, astonished. It was one rare instance where a song made me breathless. I pulled the car over in the black of night and just let it fall all over me. It was an incredibly heavy feeling, although intensely comforting. Indeed, it felt like utterly harsh truths were being spoken, being sung—but there was a great comfort in that. Like being pushed to the edge of a precipice and feeling the wind blow by just before falling, but without any sense of fear. It was frightening relief. Staggering, levelling stuff. After I came out of it, it was whoa-ok-here-we-are-what-just-happened-got-to-get-to-the-hospital-in-one-piece. Knocked over.

Every single word in “Althea” strikes with thunderous truth. It’s astonishing. Sincerity, truth, humility, heartbreak, warning, caution, regret, loss—caution. Caution prevails there. As you say, on the surface it feels like the anguish(es) of romantic love—which on a level feels right—but goodness, one comes away from this song realizing that somehow it is about everything—every single thing that matters. It feels like a guide about how to live, or what it is to live terribly. The word gets tossed about easily, but I experienced this song, the first time I heard it that night, as simply—essential. Yes—it contains the very essence of what is concerning.

What a gift these folks—Garcia and Hunter—bestowed upon the world. It’s a colossal, mammoth work of art.

Returning from the hospital, I soon learned it and made a recording, lamenting the situation my father found himself in, connected to that, unable to help him, trying to do anything productive. I sent the demo to Gillian (Rivers), alchemist of all things strings playing, and she understood without my having to explain, returning these exquisite, sweeping parts. I recorded it properly with my dear friend Darshan (Jesrani), capturer extraordinaire, at his wondrous place in the city. Then Pete (Kember) got hold of it all in Portugal, lacing things with his remarkable, singular touch, playing, mixing and production.

This song is a warning. One which I’d like to heed, if I can.

PM: “Are You Ready” is the extended “AM” version of the same title, taken from your latest LP, Days Go By. Within its scintillating soundscape, you sing again of the frustrations of romantic attachment and the fact that nothing ultimately lasts in the temporal world, even love itself. First, I wonder why you chose to rework this particular track above all your other recent releases? And secondly, akin to “Althea”, I intuit perhaps that another level of meaning permeates its elegant and elusive sounds. Could you say something about that?

Cheval Sombre: The truth is that these songs arrive unexpectedly—I’ll find myself in a difficult situation though, and they (the songs) sometimes descend. I was telling a friend that I felt that “Are You Ready” is an apocalypse song—the moment when the light throws itself upon a dark and destructive reality, and we see clearly what is. But there is power in that kind of recognition—one becomes conscious, and drawn toward the light. The landscape can be desolate, but look carefully, and there are always splinters of light. Dean (Wareham) and Pete (Kember) understood this subtle point, so graceful their parts, full of elegance, luminous amidst troubles, disintegration, emptiness.

I always find it difficult to distil the meaning of any particular song—meaning is elusive to me, even in my own work. But I can say that in there (as you rightly heard) is romantic dissolution, but also the collapse of all that inundates us, viciously, relentlessly, daily. Call it expectations, call it the news—it’s all just noise, in the end. The song wonders about what our relationship to silence is—perhaps it’s a little worried about that. I suppose it’s a worried blues of a kind.

When Pete (Kember) sent over this mix, the truth is that I had never really heard anything like it from him, or anyone else. The weightlessness he achieved just floored me. The song just—floats. I remember when I first heard it—I was walking through the woods when the pandemic first struck in New York. It was a terrifying time, but Pete somehow narrated it all precisely in sound, and somehow managed to create a comforting blanket, too.

PM: The final track is another cover, this time of Dire Straits’ “So Far Away”. An understated gem to end the EP, its emotionally and musically raw vulnerability is particularly poignant, aptly emphasized by the pulse of cicadas, the cry of a police siren, the hiss of the sea. Utter magic! You have spoken of heartbreaking circumstances leading up to its inception. Would you be willing to expand a little on that and why this song in particular means so much to you?

Cheval Sombre: Understatement has always hit me harder than volume, pizazz, drama, scenes. Ever have someone whisper in your ear? A secret resounds. I lean in. What’s there?

And quiet has brought me to some miraculous places. I’ve appreciated artists who, in one way or another, made demands on me as a listener. I like having to lean in—then there is a real exchange—everyone gives.

“So Far Away” was on the radio all the time when I was a kid. It just stuck with me all these years as a lovely, melancholic, pretty, but tough song. I never thought it would apply to me personally, but then—it did. I got the guitar out, (sort of) learned it, and hit record. This version is the one and only time I recorded it. That night was awful and beautiful and truthfully I don’t want to think about it any longer. That the natural thrumming of life made its way into the recording brings a quiet joy, though. There is always much more to life than what we may be perceiving in any given moment. A symphony ever plays.