La femme inspiratrice

“Habits gradually change the face of one’s life

as time changes one’s physical face;

& one does not know it.”

—Virginia Woolf, diary entry, 13th April 1929

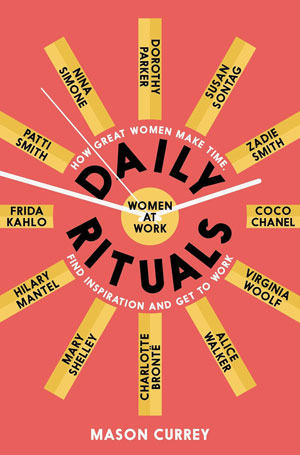

IN HIS FOLLOW-UP book, for which he offers an introductory apology, Mason Currey brings us another brilliant offering of the daily habits of writers at their desks and artists in their studios, this time focussing solely on women. Feeling his previous book, Daily Rituals: How Great Minds Make Time, Find Inspiration and Get to Work, had a gender imbalance in its presentation, Currey seeks to correct the disparity by publishing a highly digestible companion.

Despite the inclusion only of the “fairer sex”, Daily Rituals: How Great Women Make Time, Find Inspiration and Get to Work is structured around the same premise; namely, the unique and often quirky quotidian habits of female writers and artists, once again adroitly compiled for dipping into, when one’s own muse is found significantly wanting or simply the pure delight of having a window into a creative’s intimate life. Here, we consider the routines of sculptor Harriet Hosmer, painter Agnes Martin, poet Emily Dickinson, and writers Hilary Mantel and Virginia Woolf.

Needless to say, in this world where definitions of womanhood are more and more on shaky ground (gentle reader, this is not a discussion I personally wish to get embroiled in), Currey himself states his cause:

Of course, I’m aware of the danger of separating ‘women artists’ from just artists (and in a book by a man, no less!). Many of the women profiled here were used to seeing accomplishments tied to their gender, and none of them liked it. As the painter Grace Hartigan told an interviewer, ‘I was never conscious of being a female artist and I resent being called a woman artist. I’m an artist.’ For what it’s worth, I have endeavoured to treat the artists in this collection in the same manner as I did the men (and women) in the original volume, with entries that draw on letters, diaries, interviews, and secondhand accounts to assemble capsule portraits of how they got their work done on a daily basis.

Harriet Hosmer

(1830–1908)

sculptor

‘I am as busy as a whole hive of bees, one bee is not sufficient to represent all the irons I have in the fire,’ the American neoclassical sculptor wrote from her studio in Rome in 1870. Ever since arriving in the Eternal City as an eager apprentice 18 years earlier, Hosmer had been perpetually at work, sculpting most days from dawn until dinner. ‘She was never idle,’ her friend Cornelia Carr remembered.’ Her busy brain was unceasingly at work on favourite designs, and she was happy in plans for future activity.’

Her dedication did not leave much time for a personal life; indeed, Hosmer swore off any romantic attachments at a young age, believing that they were too compromising for a female artist. ‘I am the only faithful worshipper of Celibacy, and her service becomes more fascinating the longer I remain in it,’ she wrote in the summer of 1854, four years after arriving in Rome.

‘Even if so inclined, an artist has no business to marry. For a man, it may be well enough, but for a woman on whom matrimonial duties and care weigh more heavily, it is a moral wrong, I think, for she must neglect her profession and her family, becoming neither a good wife and mother nor a good artist. My ambition is to become the latter, so I wage an eternal feud with the consolidating knot.’

Agnes Martin

(1912–2004)

painter

‘I have a vacant mind, in order to do exactly what inspiration calls for,’ the Canadian American painter said in 1997. 21 years earlier, she had told another interviewer much the same thing: ‘Inspiration comes from a clear mind. Right straight through. We have nothing to do with it.’ But inspiration, for Martin, didn’t simply arrive; it had to be courted, and it was essential that the artist create the proper physical conditions for it to flourish. ‘The most important thing is to have a studio and established and preserve its atmosphere,’ Martin wrote.

‘You must have a studio no matter what kind of artist you are. A musician who must practise in the living room is at a tremendous disadvantage. You must gather together in your studio all of your sensibilities and when they are gathered you must not be disturbed. The murdered inspirations and loss of art work due to interruptions and shattered studio atmosphere are unassessable.’

As for an artist’s working hours—they should be long; otherwise, Martin wasn’t particularly interested in work schedules. ‘I don’t get up in the morning until I know exactly what I’m going to do,’ she said. ‘Sometimes, I stay in bed until about three in the afternoon, without any breakfast. You see, I have a visual image. But then to accurately put it down is a long, long way from just knowing what you’re going to do.’ Again, the crucial component for Martin was vast stretches of uninterrupted time, with a near-total absence of competing obligations—and, most important, no meddling from neighbours or visitors. ‘When you’re with other people, your mind isn’t your own,’ she said.

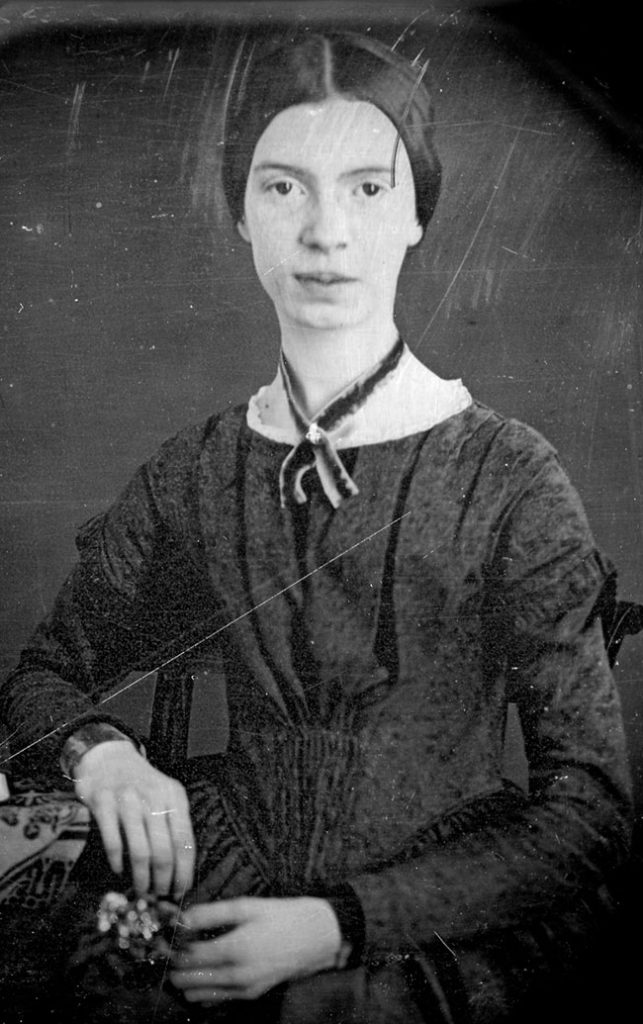

Emily Dickinson

(1830–1886)

poet

‘At 6. o’clock, we all rise. We breakfast at 7. Our study hours begin at 8. At 9. we all meet in Seminary Hall, for devotions. At 10 1/4. I recite a review of Ancient History, in connection with which we read Goldsmith & Grimshaw [a pair of history textbooks]. At .11 I recite a lesson in “Pope’s Essay on Man” which is merely transposition.

At .12, I practise Calisthenics & at 12 1/4 read until dinner, which is at 12 1/2 & after dinner, from 1 1/2 until 2 I sing in Seminary Hall. From 2 3/4 until 3 3/4. I practise upon the Piano. At 3 3/4 I go to Sections, where are we give in all our accounts of the day, including, Absence—Tardiness—Communications—Breaking Silent Study hours—Receiving Company in our rooms & ten thousand other things, which I will not take time or place to mention.

At 4 1/2, we go into Seminary Hall, & receive advice from Miss. Lyon in the form of lecture. We have Supper at 6. & silent-study hours from then until retiring bell, which rings at 8 3/4, but the tardy bell does not ring until 9 3/4, so that we dont [sic] often obey the first warning to retire.

Hilary Mantel

(1952–2022)

writer

‘Some writers claim to extrude a book at an even rate like toothpaste from a tube, or to build a story like a wall, so many feet per day … They sit at their desk and knock off their word quota, then frisk into their leisure evening, preening themselves.

‘This is so alien to me that it might be another trade entirely. Writing lectures or reviews—any kind of non-fiction—seems to me a job like any other: allocate your time, marshall your resources, just get on with it. But fiction makes me the servant of a process that has no clear beginning and end or method of measuring achievement. I don’t write in sequence. I may have a dozen versions of a single scene. I might spend a week threading an image through a story, but moving the narrative not an inch. A book grows according to a subtle and deep-laid plan. At the end, I see what the plan was …’

To other writers who get stuck, Mantel advises getting away from the desk: ‘Take a walk, take a bath, go to sleep, make a pie, draw, listen to music, meditate, exercise; whatever you do, don’t just sit there scowling at the problem,’ she has written. ‘But don’t make telephone calls or go to a party; if you do, other people’s words will pour in where your lost words should be. Open a gap for them, create a space. Be patient.’

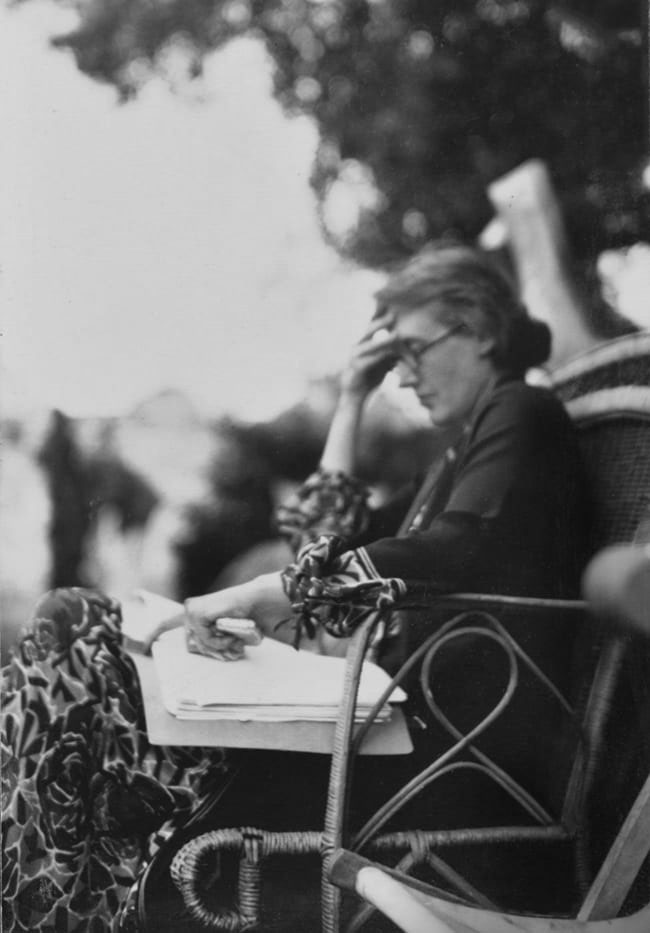

Virginia Woolf

(1882–1941)

writer

‘A good day—a bad day—so it goes on,’ Woolf wrote in her diary in June 1936. ‘Few people can be so tortured by writing as I am. Only Flaubert I think.’ Like Flaubert, Woolf’s work habits were regular and orderly: for most of her life, she’s stuck to a daily routine of writing from 10:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m., and she used her diary to keep track of her output and chide herself for unproductive days. ‘She structured her working life by self-imposed routines which were essential to her,’ the biography Hermione Lee has written. ‘Writing (fiction or reviews) was done in the first part of the morning; just before or after lunch was for revising (or walking, or printing). After tea was for diary or letter-writing; the evenings were for reading (or seeing people). She never wrote at night. ‘How great writers write at night, I don’t know,’ Woolf noted in her diary. ‘Its [sic] an age since I tried, & I find my head full of pillow stuffing: hot; inchoate.’

The regular schedule was encouraged by Woolf’s husband, Leonard, who had additional reasons for preferring a steady, calm life. Shortly after their marriage in 1912, Virginia suffered a prolonged and harrowing mental breakdown—one of several in her life—and from then on Leonard assumed the role of his wife’s guardian, caretaker, and quasi- parent, cajoling her into following doctors’ orders; supervizing her social life to make sure she didn’t get overexcited; keeping track of her diet, her writing, and even her menstrual periods; and deciding, after consultations with several doctors and with Virginia’s sister, Vanessa Bell, that they should forgo having children, under the belief that pregnancy could ruin Virginia’s fragile mental health.

Many biographies have interpreted Leonard’s behaviour as overly controlling, but there’s no doubt that he believed in her writing and created conditions favourable for it to flourish. ‘L. thinks my writing the best part of me,’ Virginia wrote in a letter. ‘We’re going to work very hard.’ They certainly did that. ‘Neither of us ever took a day’s holiday unless we were too ill to work or unless we went away on a regular and, as it were, authorized holiday,’ Leonard wrote. ‘We should have felt it to be not merely wrong but unpleasant not to work every morning for seven days a week and for about 11 months a year.’

Post Notes

- Feature image: Virginia Woolf, Emily Dickinson, Agnes Martin, Hilary Mantel, Harriet Hosmer, Public Domain & Fair Use

- Mason Currey’s website

- Mason Currey: Daily Rituals

- The Spirituality of Jane Austen

- Kathleen Raine: The Land Unknown

- Virginia Woolf: A Room of One’s Own

- Suzanne Moss: Seeking Sanctuary

- Agnes Martin: Writings

- Hannah Peschar Sculpture Garden & Zen Master Ryokan

- Paula Marvelly: The Sacred Feminine Through the Ages

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme