Ethics of style

“We possess art lest we perish of the truth.”

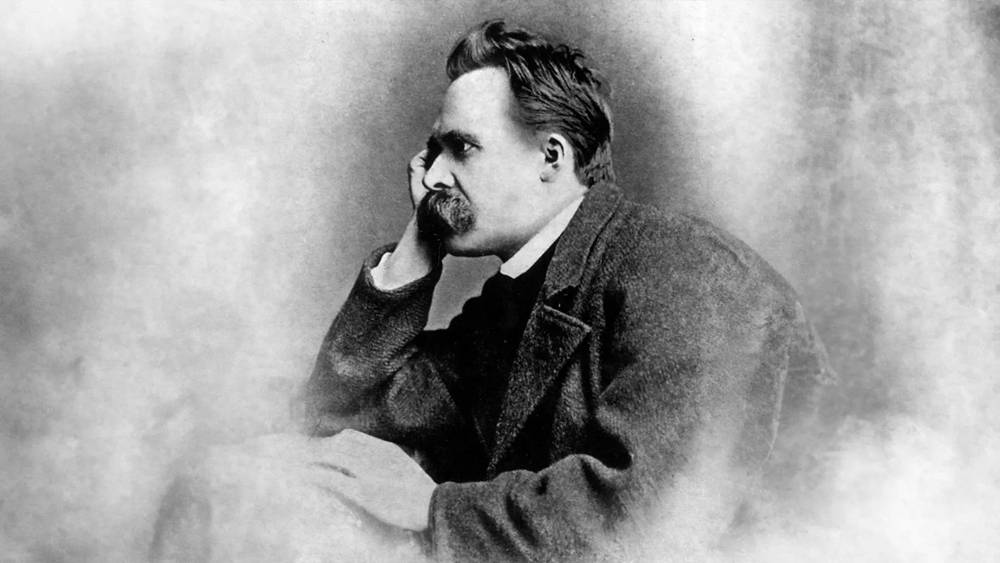

—Friedrich Nietzsche

YAHIA LABABIDI is a critically acclaimed Lebanese-Egyptian writer and poet, whose work has been featured across the media and generously endorsed by President Obama’s inaugural poet, Richard Blanco. Nominated for a Pushcart Prize five times, he has also participated in numerous international poetry festivals throughout the world, his writing translated into several languages worldwide.

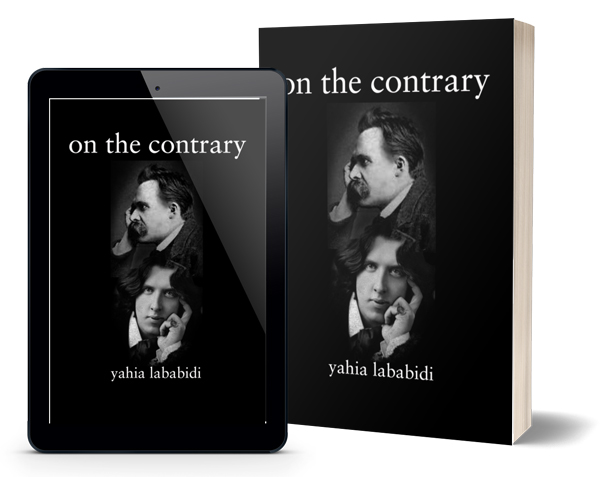

In his latest contribution to The Culturium, Yahia’s spellbinding essay is an intellectual exploration of the lives, philosophies and literary styles of Oscar Wilde and Friedrich Nietzsche, two influential figures of the late 19th century. Drawing parallels between their ideas, personalities and contributions to art, metaphysics and culture, despite their vastly different lives and circumstances, Yahia’s thesis forms the premise for his forthcoming book, On the Contrary: The Great Contrarians, Oscar Wilde & Friedrich Nietzsche to be published by Fomite Press on 15th October 2025.

Perhaps slightly begrudging Wilde his fame and posthumous status as a martyr, Bernard Shaw once indulged a hypothetical exercise: how would Wilde have been remembered had he died before his scandal and imprisonment? ‘Oscar,’ he wrote, ‘would still have been recalled as a wit and a dandy, with a niche beside William Congreve in the drama. A volume of his aphorisms would have stood creditably beside La Rochefoucauld’s Maxims.’ What of Nietzsche, if he had died sane? He, too, would have cut a striking figure in the annals of literature and psychology, and found a place beside the modern philosophers, if only for the boldness of his experiment.

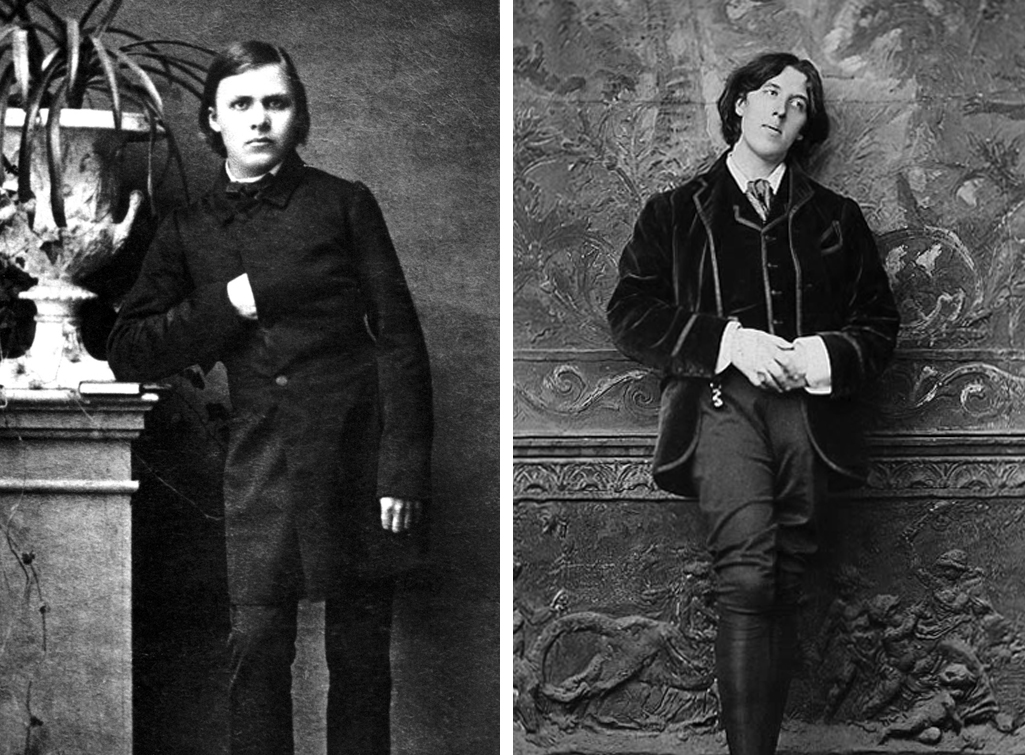

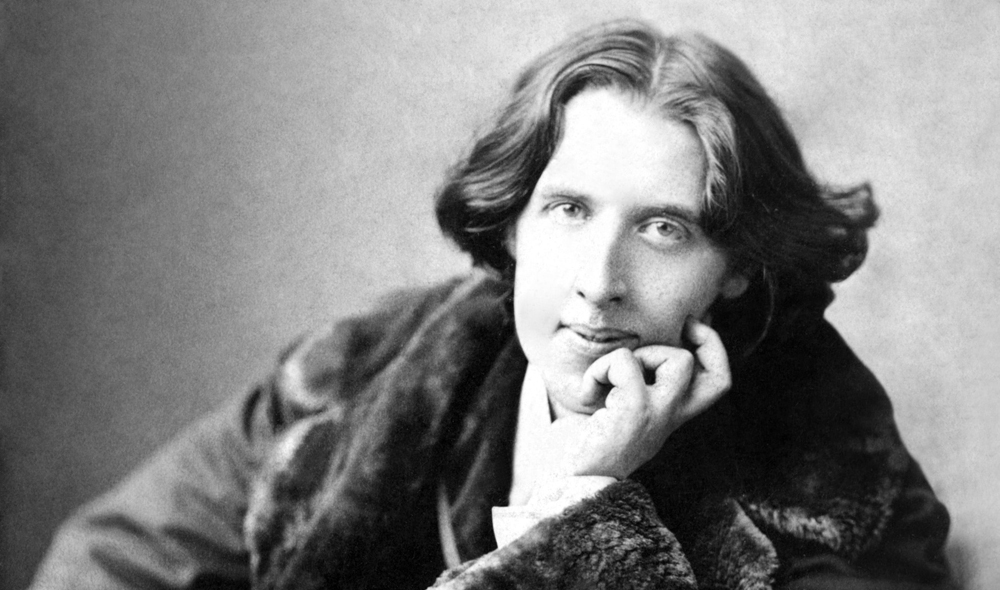

At times, beauty may feel like the last form of truth available to us. For Oscar Wilde (16th October 1854–30th November 1900) and Friedrich Nietzsche (15th October 1844–25th August 1900), beauty was reason and justification for existence. They believed that aesthetics carried ethical weight and that lives were shaped by how one lived, spoke and suffered. Both sought to restore grace to the moral life, to make of existence a kind of art.

Their outward lives were unalike. Wilde moved through glittering salons, the toast of London drawing rooms, a master of epigram and performance. Nietzsche walked alone among mountains, a solitary thinker who composed prose like poetry, seeking clarity in silence and thin air. One spoke in laughter, the other in lightning. Yet each was animated by a similar hunger: to fashion a philosophy that could teach the soul how to live, that could guide us through disorder and despair.

Both men were extremists who recognized that extremes are closer to one another than to moderation, which so eluded them. Nietzsche observed that ‘extreme positions are not succeeded by moderate ones but by contrary extremes’. Wilde, too, was bewitched by extremity, by the fascination of living entirely through art and of testing how far the aesthetic could carry the moral self. In seeing both sides of an argument at once, each risked becoming cross-eyed, yet their contradictions are what make them human.

They turned to Ancient Greece for harmony and measure, to writers who taught that beauty is inseparable from goodness. They also looked to France, to La Rochefoucauld and Baudelaire, who gave language the precision of a blade and the delicacy of music. Beneath their differences ran a shared conviction that ideas are hollow unless incarnated through the rhythm and radiance of language. For these moral stylists, thought had to possess colour and grace. In their hands, prose became revelation.

Nietzsche wrote that ‘to give style to one’s character’ is a rare and noble art. The self, in his eyes, was clay to be shaped, refined through effort and awareness until one’s very flaws might be integrated into a larger beauty. Wilde, in another register, expressed a similar faith in transformation: ‘One should either be a work of art or wear a work of art.’ What each meant was that form reveals spirit, that the way we carry ourselves becomes our truest confession.

Both were wounded spirits who sought to transfigure their wounds. Nietzsche’s chronic pain and loneliness became the crucible of amor fati, the wholehearted love of one’s fate. Through suffering, he discovered affirmation. Wilde’s humiliation and imprisonment revealed a parallel grace. In De Profundis, he writes of his disgrace as purification, the stripping away of pride that left compassion behind, making him naked for the first time. For each, endurance became imagination; from defeat, they distilled insight. Through pain, both learned how suffering can be made radiant.

Language was their chosen instrument of salvation. The aphorism, brief and charged, suited their desire for intensity—brief enough to strike like lightning, musical enough to linger in the mind. Their aphorisms are not pronouncements but provocations, seeds for reflection, sparks struck against convention. In a sentence, they sought to condense whole systems of thought, to make wisdom portable and memorable. Wilde’s aphorisms shimmer with wit, yet beneath their sparkle lies a grave insistence that life without beauty is a kind of blasphemy. Nietzsche’s thunderous declarations conceal a similar tenderness: behind the call to strength stands a plea for sincerity, for the courage to bear reality without illusion.

Their reverence for appearances was also profound. ‘The Greeks,’ Nietzsche once observed, ‘were superficial—out of profundity.’ To remain at the surface with courage, to love the visible world in all its fragility, was for him a spiritual discipline. Wilde’s echo is well known: ‘It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances.’ They both understood that the visible is sacred, that beauty reveals truth through suggestion. The surface, rightly perceived, is depth made visible—a meeting place of spirit and matter where wonder is restored.

This worship of beauty was inseparable from a love of play. ‘Not by wrath, but by laughter, do we slay,” declares Nietzsche’s Zarathustra. Wilde, with the same mischievous wisdom, assures us that life is too important to be taken solemnly. Their laughter was faith—a defiant joy that refuses despair, a defense of the sacred from sentimentality. Both saw in play the secret of endurance, the renewal of wonder, the only answer to nihilism. To keep one’s heart light in dark times, to bear the weight of being with grace, to smile at tragedy without turning away from it, is a moral victory.

Masks fascinated them. ‘Give a man a mask and he will tell you the truth,’ Wilde wrote. Nietzsche confessed that every deep soul must wear one. They knew that identity is fluid, a series of roles through which one approaches authenticity. A mask may serve revelation, allowing truth to speak indirectly and survive exposure. Both made theatre of their thought: Wilde through conversation and costume, Nietzsche through parable and poetry. In an age that worships confession, their artful reserve feels newly wise.

If they erred, it was through the extravagance of their gifts. ‘Body and soul, I am more of a battlefield than a human being,’ Nietzsche confessed. Wilde’s admission is more theatrical but no less raw: ‘I have been a spendthrift of my genius, and to myself a wastrel of my heart.’ Their brilliance, at times, consumed them—Wilde’s appetite for admiration and Nietzsche’s relentless solitude carrying both to extremes. They paid dearly for the courage to live as they thought and to think as they lived. Yet their excesses are part of their lesson. They remind us that brilliance and breakdown, art and affliction, are often contiguous realms. When Nietzsche fell silent into madness and Wilde into disgrace, each revealed the peril of living at the edge of one’s own flame. Each knew that the enemy is within. Their philosophies, for all their defiance, are acts of contrition.

Both believed that the self must be shaped through inner discipline rather than imposed law. ‘Become who you are,’ urged Nietzsche, borrowing from the Greeks. Wilde answered that ‘the development of the individual is the only aim of life’. They rejected conformity from a conviction that the world is renewed only by singular souls. True morality, for them, was a creative act—the crafting of one’s being according to the measure of beauty. They treated existence as an unfinished poem, to be revised in courage and imagination.

Their faith in crisis as creative force speaks to us still. ‘Every great progress must be preceded by a partial weakening,’ Nietzsche observed. Wilde echoed him: ‘Discontent is the first step in the progress of a man or nation.’ Both affirmed that renewal grows from ruin, that the soul grows through contradiction. Out of the ruins of certainty, they built new forms of faith.

To speak of Wilde and Nietzsche today is to speak of ourselves. They foresaw an age, like ours, suspicious of absolutes yet hungry for meaning. We live amid surfaces that glitter without depth, among masks and moral panics, craving authenticity yet drawn to display. We do not find them as outrageous as their contemporaries did. They seem, if anything, nearer to us—our interlocutors across time. We recognize in their contradictions our own divided condition: the yearning for faith and the distrust of authority, the desire for beauty and the fear of sentimentality. They remind us that to live honestly is to live experimentally, to accept that error, too, is a teacher.

Wilde and Nietzsche offer a different model: an ethics born of imagination, a spirituality rooted in art. They ask us to live deliberately, to speak with care, to find dignity even in fracture. For them, the highest faith was creation—the power to shape meaning from chaos, to make of life something worthy of contemplation.

Art, in their hands, became a means of reverence. Wilde treated beauty as prayer, a bridge to love. Nietzsche saw it as gratitude for existence itself, ‘the great stimulant to life’. Their example teaches that refinement of style is inseparable from refinement of spirit—to cultivate taste, patience and sensitivity is to cultivate the capacity to live and love. They show that art, rightly understood, is an education of the heart.

In the end, both became examples rather than doctrines. They created of themselves a living text, open to interpretation. Their legacy is one of generosity. They extend to us a renewed sense of possibility, a conviction that spirit and style can still redeem one another. Through them we glimpse a morality of beauty, in which clarity is compassion and form a kind of faith.

To write well, to speak beautifully, to live with attention, is to honour creation. They challenge us to make our lives artful, in reverence—to refine perception until compassion and clarity become indistinguishable. They remind us that the purpose of art is revelation and that beauty has the power to heal what despair divides.

They leave us this parting wisdom: that laughter can be a kind of prayer; and one may be serious without losing delight. In Wilde and Nietzsche, aesthetics and ethics meet as long-separated lovers. They remain prophets of modernity and cautionary saints. Through them, we recover faith in the possibilities of the human spirit. They whisper, still, that style, at its highest, is the signature of the soul.

Post Notes

- Feature image: Napoleon Sarony, Oscar Wilde & Unknown, Friedrich Nietzsche

- Yahia Lababidi on Poets & Writers

- Yahia Lababidi on Twitter

- Yahia Lababidi: Revolutions of the Heart

- Yahia Lababidi: Desert Songs

- Yahia Lababidi: What Remains to be Said

- Rainer Maria Rilke: Letters to a Young Poet

- Mark Rothko: The Artist’s Reality

- Agnes Martin: Writings

- Kahlil Gibran: Poet, Painter, Prophet

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme