Training the mind and body to become one

“I learned to lose myself so effortlessly in the breathing

that I sometimes had the feeling

that I myself was not breathing but

—strange as this may sound—

being breathed.”

AFTER WATCHING THE magnificent TV series of James Clavell’s Shōgun (2024) streamed on Disney + recently, I had a resurgence of interest in all things Japanese and decided to return to the classic text, Zen in the Art of Archery, by German philosopher, Eugen Herrigal (20th March 1884–18th April 1955), to assuage my thirst. Employed as a professor at the University of Tokyo between the First and Second World Wars, Herrigal’s six-year apprenticeship with master archer, Awa Kenzō, was initially undertaken as a means of becoming better acquainted with Asian culture.

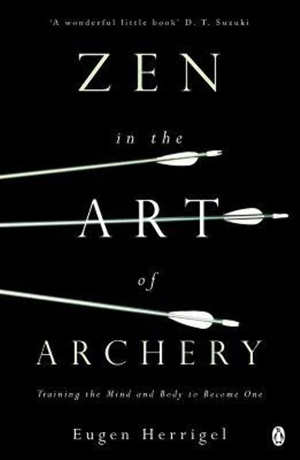

Written with poetic restraint and philosophical insight (beautifully translated by R. F. C. Hull and accompanied by a wonderful foreword by D. T. Suzuki), this slim volume is far from being a technical manual on martial discipline ordinarily practised by a samurai warrior (known as kyūjutsu); rather, it explores how the mental and spiritual discipline of the way of the bow serves as a gateway to egolessness and purposeless detachment (known as kyūdō). Indeed, for Herrigel, the art of “loosening” or releasing the arrow without volition becomes an intimate experience and living expression of the “Great Doctrine”, namely Dhyana Buddhism or Zen as it is known in Japan.

Despite the book’s elegant and timeless wisdom, we must also remember it comes with an unsettling paradox—Herrigel himself was a Nazi sympathiser, a detail often glossed over but impossible to ignore. Inasmuch as this does not invalidate the text per se, in our own search for truth, we must reconcile the fact that metaphysical revelation may pass through imperfect vessels. Casting judgement aside, what matters most is not the personality of the teacher (or writer) but the presence of the teaching itself. Zen in the Art of Archery, therefore, remains a quietly luminous entry point into the mystery of no-mind, where the very act of drawing the bow and releasing the arrow becomes a metaphor for all true spiritual practice, in spite of the vicissitudes of the archer: the letting go of self into the silence from which all things arise.

The demand that the door of the senses be closed is not met by turning energetically away from the sensible world, but rather by a readiness to yield without resistance. In order that this actionless activity may be accomplished instinctively, the soul needs an inner hold, and it wins it by concentrating on breathing. This is performed consciously and with a conscientiousness that borders on the pedantic. The breathing in, like the breathing out, is practised again and again by itself with the utmost care. One does not have to wait long for results. The more one concentrates on breathing, the more the external stimuli fade into the background. They sink away in a kind of muffled roar which one hears with only half an ear at first, and in the end one finds it no more disturbing than the distant roar of the sea, which, once one has grown accustomed to it, is no longer perceived. In due course one even grows immune to larger stimuli, and at the same time detachment from them becomes easier and quicker. Care has only to be taken that the body is relaxed whether standing, sitting, or lying, and if one then concentrates on breathing one soon feels oneself shut in by impermeable layers of silence. One only knows and feels that one breathes. And, to detach oneself from this feeling and knowing, no fresh decision is required, for the breathing slows down of its own accord, becomes more and more economical in the use of breath, and finally, slipping by degrees into a blurred monotone, escapes one’s attention altogether.

This exquisite state of unconcerned immersion in oneself is not, unfortunately, of long duration. It is liable to be disturbed from inside. As though sprung from nowhere, moods, feelings, desires, worries and even thoughts incontinently rise up, in a meaningless jumble, and the more far-fetched and preposterous they are, and the less they have to do with that on which one has fixed one’s consciousness, the more tenaciously they hang on. It is as though they wanted to avenge themselves on unconsciousness for having, through concentration, touched upon realms it would otherwise never reach. The only successful way of rendering this disturbance inoperative is to keep on breathing quietly and unconcernedly, to enter into friendly relations with whatever appears on the scene, to accustom oneself to it, to look at it equably and at last grow weary of looking. In this way gradually gets into a state which resembles the melting drowsiness on the verge of sleep.

—Eugen Herrigel, Zen in the Art of Archery

Post Notes

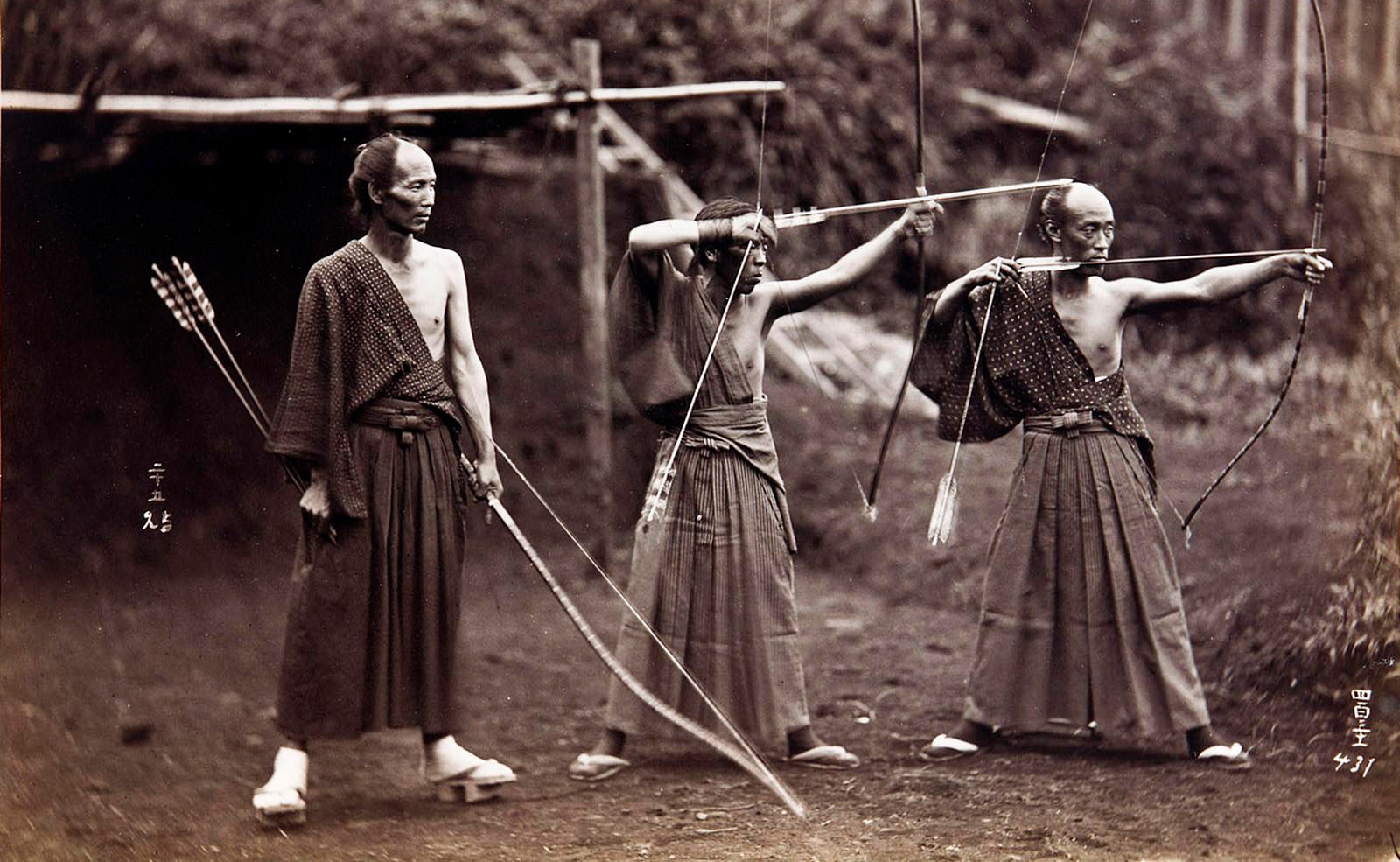

- Feature image: Photographer unidentified, Three Archers, Japan, 1860-ca. 1900,

Henry and Nancy Rosin Collection of Early Photography of Japan, Smithsonian Institution - Matsuo Bashō: The Narrow Road to the Deep North

- Matsuo Bashō: Deep Silence

- Matsuo Bashō et al.: Four Huts

- Ajahn Sumedho: The Sound of Silence

- Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching

- Gabriel Rosenstock & Ron Rosenstock: Haiku Enlightenment

- Kaneto Shindo: The Naked Island

- Hannah Peschar Sculpture Garden & Zen Master Ryokan

- Shūsaku Endō: Silence

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme