Image: Public Domain

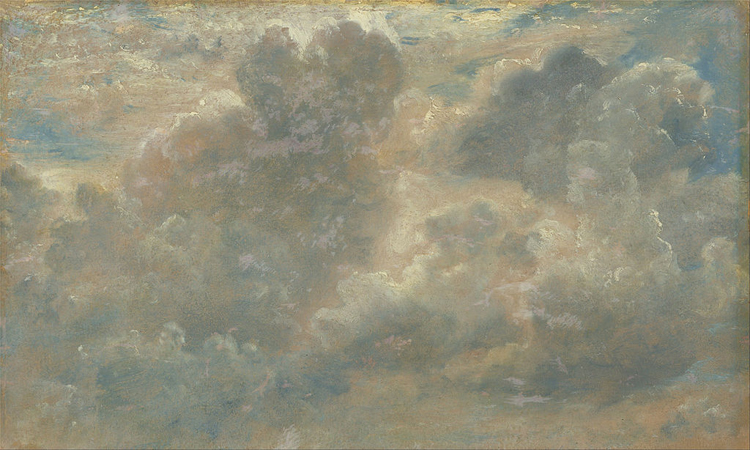

The art of gazing at clouds

“I am the daughter of Earth and Water,

And the nursling of the Sky;

I pass through the pores of the ocean and shores;

I change, but I cannot die.”

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH’S LINE, “I wandered lonely as a cloud”, is probably one of the most immortal moments of self-reflection in the whole canon of British poetry, etched deeply into the subconscious of any aspiring student of English; indeed the metaphor of inclement weather has long been used in literature, both of the West and East, to represent inner emotional states of the mind.

Perhaps lesser known, and yet no less profound, is “The Cloud” (1820) by Percy Bysshe Shelley (4th August 1792–8th July 1822), an allegorical meditation on the cycle of dissolution and rebirth. Told from the perspective of the cloud itself, the poem explores the transient nature of all sentient life through the sacred rhythm of metempsychosis.

And yet, while it acknowledges the mutability of creation, the cloud finds itself deeply amused for it understands that, behind its meteorological shapeshifting, the fundamental reality of life is eternal joy, sustained by the power of love.

Image: Public Domain

Shelley was one of the major purveyors of the Romantic literary movement in Britain during the first half of the nineteenth century. As a reaction to the Industrial Revolution and the prevailing “scientific method”, it championed feeling and emotion as the dominant and most meaningful forces within man.

Moreover, Romanticism recognized an even deeper aesthetic experience, wonderment in the face of nature, often leading to awe and unbounded awareness. Indeed, parallels to mystic philosophy are obvious in Shelley’s exquisite poetry; in the final stanza, the transcendental verse of Walt Whitman, the Gnostic Gospels and even the Indian Upanishads often come to mind.

As with so many great artists of the past, it was only upon his death, two years after the publication of “The Cloud”, that Shelley’s writings were even appreciated. His nephological legacy is one which, in my humble opinion, has yet to be surpassed.

I bring fresh showers for the thirsting flowers,

From the seas and the streams;

I bear light shade for the leaves when laid

In their noonday dreams.

From my wings are shaken the dews that waken

The sweet buds every one,

When rocked to rest on their mother’s breast,

As she dances about the sun.

I wield the flail of the lashing hail,

And whiten the green plains under,

And then again I dissolve it in rain,

And laugh as I pass in thunder.

Image: Public Domain

I sift the snow on the mountains below,

And their great pines groan aghast;

And all the night ’tis my pillow white,

While I sleep in the arms of the blast.

Sublime on the towers of my skiey bowers,

Lightning my pilot sits;

In a cavern under is fettered the thunder,

It struggles and howls at fits;

Over earth and ocean, with gentle motion,

This pilot is guiding me,

Lured by the love of the genii that move

In the depths of the purple sea;

Over the rills, and the crags, and the hills,

Over the lakes and the plains,

Wherever he dream, under mountain or stream,

The Spirit he loves remains;

And I all the while bask in Heaven’s blue smile,

Whilst he is dissolving in rains.

Image: Public Domain

The sanguine Sunrise, with his meteor eyes,

And his burning plumes outspread,

Leaps on the back of my sailing rack,

When the morning star shines dead;

As on the jag of a mountain crag,

Which an earthquake rocks and swings,

An eagle alit one moment may sit

In the light of its golden wings.

And when Sunset may breathe, from the lit sea beneath,

Its ardours of rest and of love,

And the crimson pall of eve may fall

From the depth of Heaven above,

With wings folded I rest, on mine aëry nest,

As still as a brooding dove.

Image: Public Domain

That orbèd maiden with white fire laden,

Whom mortals call the Moon,

Glides glimmering o’er my fleece-like floor,

By the midnight breezes strewn;

And wherever the beat of her unseen feet,

Which only the angels hear,

May have broken the woof of my tent’s thin roof,

The stars peep behind her and peer;

And I laugh to see them whirl and flee,

Like a swarm of golden bees,

When I widen the rent in my wind-built tent,

Till calm the rivers, lakes, and seas,

Like strips of the sky fallen through me on high,

Are each paved with the moon and these.

Image: Public Domain

I bind the Sun’s throne with a burning zone,

And the Moon’s with a girdle of pearl;

The volcanoes are dim, and the stars reel and swim,

When the whirlwinds my banner unfurl.

From cape to cape, with a bridge-like shape,

Over a torrent sea,

Sunbeam-proof, I hang like a roof,

The mountains its columns be.

The triumphal arch through which I march

With hurricane, fire, and snow,

When the Powers of the air are chained to my chair,

Is the million-coloured bow;

The sphere-fire above its soft colours wove,

While the moist Earth was laughing below.

Image: Public Domain

I am the daughter of Earth and Water,

And the nursling of the Sky;

I pass through the pores of the ocean and shores;

I change, but I cannot die.

For after the rain when with never a stain

The pavilion of Heaven is bare,

And the winds and sunbeams with their convex gleams

Build up the blue dome of air,

I silently laugh at my own cenotaph,

And out of the caverns of rain,

Like a child from the womb, like a ghost from the tomb,

I arise and unbuild it again.

Post Notes

- Percy Bysshe Shelley at The Poetry Foundation

- John Devitt: Cloud Illusions

- William Blake: All Religions Are One

- Rousseau: Meditations of a Solitary Walker

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: Nature

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: Waldeinsamkeit

- The Cloud of Unknowing

- Wallace Stevens: Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction

- T. S. Eliot: A Man Out of Time

- Emily Dickinson: The Soul’s Superior Instants