Image: Public Domain

A contemplation in which a soul is oned with God

“So I encourage you—bow eagerly to love. Follow its humble stirrings in your heart. Let it guide you in this life and it will bring you safely to eternal bliss in the next. Love is the essence of all goodness. Without it, no kind work is ever begun or finished. Simply put, love is a goodwill in harmony with God.”

— “The Cloud of Unknowing”

IT IS ONLY in recent years that I have come to appreciate the mystical texts of the Christian teachings, having spent most of my life investigating Eastern philosophy, specifically Advaita Vedanta and the nondual message of Ramana Maharshi and Nisargadatta Maharaj. The overt religiosity and pious rhetoric of Western theology quite frankly used to turn my stomach.

Many have argued that the so-called enlightenment states of Zen, Taoism and Advaita are not the same as that elucidated upon in seminal works such as the Gnostic Gospels and the writings of the mediaeval scholar, Meister Eckhart. I now disagree for how could it be possible to have multifarious interpretations of the all-pervading, undifferentiated whole?

Indeed, the Middle Ages in Europe saw a flourishing of writers producing literature devoted to exploring transcendental levels of human experience—the Beguines, Thomas à Kempis, Julian of Norwich and the anonymous author of The Cloud of Unknowing. Composed in England (most probably in the East Midlands area) during the latter half of the fourteenth century, the Cloud is a spiritual handbook penned to an also anonymous twenty-four-year-old aspirant, instructing them in contemplative prayer and self-reflection.

At the exoteric level, the Cloud’s 75 chapters or letters contain all the familiar linguistics of the Christian teaching; however, a closer examination—made all the more accessible by Carmen Acevedo Butcher’s exquisite translation from Middle English into modern—renders an illuminated insight into the esoteric message of a mystic, whereby the mind may be infused with stillness and the heart with unconditional love.

Moreover, specific passages bear uncanny resemblances to oriental sutras and Upanishads, such is their exposition on the nature of thought, being in the present moment and the act of immersing the self in a state of unknowing, which the anonymous author deems synonymous with a “cloud”.

And yet this is no ordinary nephophilic metaphor: “When I refer to this exercise as a darkness or a cloud, I don’t want you to imagine the darkness that you get inside your house at night when you blow out a candle; nor do I want you to imagine a cloud crystallized from the moisture in the air … When I say ‘darkness’, I mean the absence of knowing. Whatever you don’t know and whatever you’ve forgotten are ‘dark’ to you because you don’t see them with your spiritual eyes. For the same reason, by ‘cloud’ I don’t mean a cloud in the sky but a cloud of unknowing between you and God.”

The tradition of “unknowing” was already well established in Western philosophy by the likes of Socrates (through the writings of Plato) and Dionysius, who spoke of the via negativa or the “negative way” —also known as apophasis—by which any attempts to describe God can only be made in terms of what the divine is actually not, such reductive practices already the very cornerstone of Eastern philosophy, whereby the path of negation is used to understand the very nature of Self.

How interesting, then, that The Cloud examines identical themes, its author in all probability, however, never even remotely aware of the nondual tradition that preceded it, thus serving only to reiterate the transcendental message of universal Truth and timeless wisdom, whatever the age or spiritual tradition.

o0o

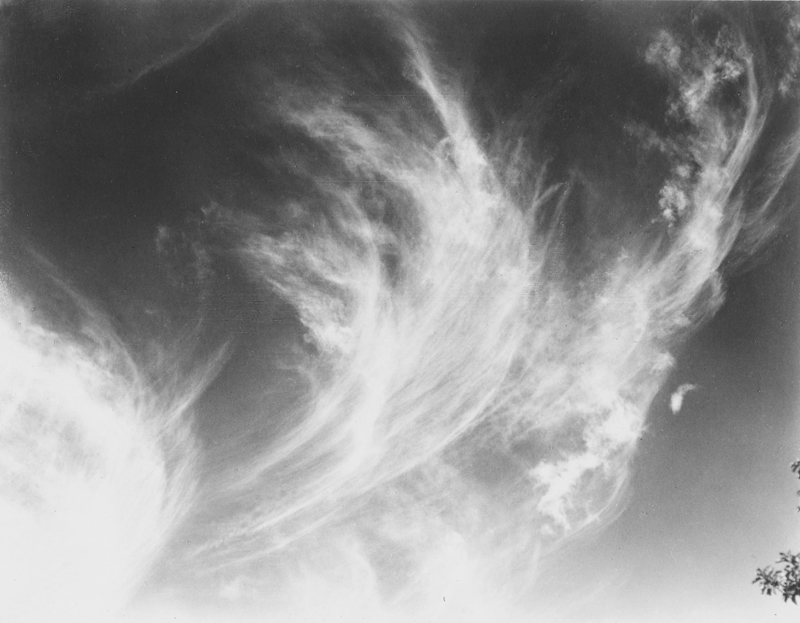

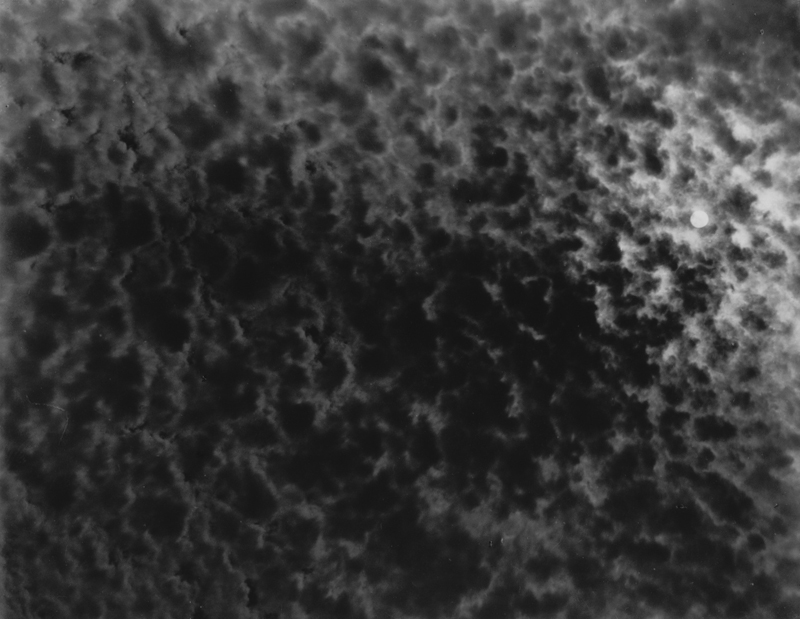

You will note that I have categorically gone against the author’s wishes and illustrated this piece with images of clouds; forgive me, gentle reader, but for the purposes of presentation, I felt American photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s beautiful cloud images were the perfect match. Termed Equivalents, Stieglitz believed that abstract forms and monochromatic contrasts could represent corresponding inner emotional and spiritual states, coined in his own inimitable words as “vibrations of the soul”.

Image: Public Domain

The first time you practise contemplation, you’ll only experience a darkness, like a cloud of unknowing. You won’t know what it is. You’ll only know that in your will you feel a simple reaching out to God. You must also know that this darkness and this cloud will always be between you and God, whatever you do. They will always keep you from seeing him clearly by the light of understanding in your intellect and will block you from feeling him fully in the sweetness of love in your emotions. So, be sure to make your home in this darkness. Stay there as long as you can, crying out to him over and over again because you love him. It’s the closest you can get to God here on earth, by waiting in this darkness and in this cloud. Work at this diligently, as I’ve asked you to, and I know God’s mercy will lead you there.

—The Cloud of Unknowing, Chapter 3

Image: Public Domain

If you ask me what sort of self-control you need to do the work of contemplation, my answer is, ‘None at all!’ In everything else you do, you should practise moderation. Avoid extremes when eating, drinking or sleeping. Also, protect your body from severe cold or heat, don’t pray or read too long and don’t spend too much time conversing with your friends. In all of these things, it’s important that you do neither too much nor too little. But in contemplation, you may throw caution to the wind. Indulge. I hope you’ll never stop doing this loving work as long as you live.

I’m not saying that it’s possible to keep the same high intensity all the time. You can’t always keep your zest for contemplation. Sometimes you’ll be sick or worn out mentally or physically and sometimes life just intervenes, pulling you down and preventing you from scaling spiritual heights. That said, I advise you to stay at it. Stick to it, in all circumstances. I mean that when something intrudes and you can’t practise contemplation, prepare for it still. Remain spiritually alert. So, for the love of God, try not to get sick. Discipline yourself as much as possible, so you won’t be the cause of your own weakness. This work requires complete tranquillity and a healthy, pure disposition of your body and soul. You must learn what rest is.

So, because you love God, take care of yourself. Stay as healthy as you can. But if illness comes your way in spite of your best efforts, be patient. Bear it with humility and wait on God’s mercy. It will be enough; all will be well. Your patience in sickness and in dealing with different kinds of problems pleases God even more than the keenest devotion in times of good health.

—The Cloud of Unknowing, Chapter 41

Image: Public Domain

The mind is such a miraculous power that any proper description of it must include this point: In a way, it really does no work. It comprehends and contains the powers of reason, will, imagination and sensuality, as well as their works. But it can’t be said to do any work itself unless you consider this comprehension as activity.

I call some of the powers of the soul major and others minor—not because the soul can be split into parts because obviously, it can’t, but its powers work with matters that can be analyzed into two categories: major or spiritual concerns and secondary or physical matters. Reason and will are soul’s two major active powers. They work solely by themselves to accomplish all spiritual advancements, with no help from the secondary powers. On the other hand, imagination and sensuality work through the body’s five senses in the arena of the material, with things both present and absent but they alone can’t help us to understand creation. We need reason and will to know virtue for being here and for doing what they do.

That’s why reason and will are called major powers because only they work in the sphere of the spiritual. Imagination and sensuality are considered secondary because their activity is confined to the body and its five senses. The mind is also regarded as a major power because it spiritually comprehends not only all of the other powers but also all of the objects on which they work.

—The Cloud of Unknowing, Chapter 63

Image: Public Domain

When distracting thoughts press down on you when they stand between you and God and stubbornly demand your attention, pretend you don’t even notice them. Try looking over their shoulders, as if you’re searching for something else, and you are. That something else is God, hidden in a cloud of unknowing. Do this and I know the work of contemplation will start getting easier for you. When tried and understood, this spiritual technique is nothing but an intense longing for God, the desire to feel and see him as we can here. This longing is true love and love always deserves the peace it wins.

There’s another trick you can try, if you want. When exhausted from fighting your thoughts, when you’re unable to put them down, fall down before them and cower like a captive or a coward overcome in battle. Give up. Accept that it’s foolish for you to fight them any longer. Do this and you’ll find that in the hands of your enemies, you are surrendering to God. Let yourself feel defeated. Accept your failure. And always keep this plan in mind because when you try it, you’ll discover that you melt like water.

—The Cloud of Unknowing, Chapter 32

Image: Public Domain

If you want to gather this focus into one word, making it easier to grasp, select a little word of one syllable, not two. The shorter the word, the more it helps the work of the spirit. God or love works well. Pick one of these or any other word you like, as long as it is one syllable. Fasten to your heart. Fix your mind on it permanently, so nothing can dislodge it.

This word will protect you. It will be your shield and spear, whether you ride out into peace or conflict. Use it to beat on the dark cloud of unknowing above you. With it, knock down every thought and they’ll lie down under the cloud of forgetting below you. Whenever an idea interrupts, you ask, ‘What do you want?’ answer with this one word. If the thought continues—if, for example, it offers out of its profound erudition to lecture you on your chosen word, expounding its etymology and connotations for you—tell it that you refuse to analyze the word, that you want your word whole, not broken into pieces. If you’re able to stick to your purpose, I’m positive the thought will go away. Why? When you refuse to let it feed on the kinds of sweet meditations that we mentioned earlier, it vanishes.

—The Cloud of Unknowing, Chapter 6

Image: Public Domain

If you want to make this cloud an integral part of your life, so you can live and work there, as I suggest, you must do one more thing: complete the cloud of unknowing with the cloud of forgetting. To the cloud of unknowing above you and between you and your God, add the cloud of forgetting beneath you, between you and creation. If the cloud of unknowing makes you feel alienated from God, that’s only because you’ve not yet put a cloud of forgetting between you and everything in creation. When I say ‘everything in creation’, I mean not only the creatures themselves but also everything they do and are, as well as the circumstances in which they find themselves. There are no exceptions. You must forget everything. Hide all created things, materal and spiritual, good and bad, under the cloud of forgetting.

Obviously, sometimes it is helpful and even necessary to analyze situations and people but the work of contemplation finds such analysis of little use. When you reflect on something going on or try to figure someone out, you’re engaging in one type of spiritual vision—the eye of your soul opens and concentrates on an idea or person in the same way that an archer focuses on a target. However, as long as you’re thinking about anything, it’s above you, an obstacle between you and God, and the more you have in your mind that is not God, the further you are from him.

—The Cloud of Unknowing, Chapter 5

Image: Public Domain

I [start] by describing for you the two kinds of lives in the Church, the active and the contemplative. The active life is lower, the contemplative higher, and both have two stages, also a lower and a higher. These two lives are complementary and so bound together that, although each is quite distinct, neither can exist without the other. The higher stage of the active life is also the lower stage of the contemplative life. That’s why you can’t be truly active unless you participate in the contemplative life and you can’t be fully contemplative unless you participate in the active life. The active life starts and ends on earth but the contemplative life begins on earth and never ends … Though the active life is anxious and there are always problems, the contemplative life sits in peace, focused on one thing.

In the lower stage of the active life, you learn genuine acts of mercy and practise loving. In the higher stage of the active life (synonymous with the lower stage of contemplative living), your spirit becomes preoccupied with looking and you start spending time in meditation. In this higher active stage, your mind steeps in remorse for your flaws and mistakes … But in the higher stage of contemplation, as far as we know it here on earth, is only darkness and the cloud of unknowing and once we are in these, we find that loving nudges lead us into a blind gazing at the naked being of God alone.

The lower stage of active life requires extroversion and takes place between you and the world under you, so to speak, while the higher stage of the active (lower stage of the contemplative) becomes interior and you start getting acquainted with yourself. But in the higher stage of the contemplative life, your interactions take place above you, between you and God. In this way, you transcend yourself, achieving by grace what you can’t do on your own—union with the God of love and freedom.

If you’re going to advance to the higher stages of the active life, temporarily stop engaging in its lower stage, just as you must suspend practice of the lower stage of the contemplative life to advance to its higher stage. That’s why when you meditate, you must not let your mind turn to your life and to things that you have done or are planning to do, even if these are good deeds. This approach will seem odd at first. That’s also why when you advance in kindness to working in the darkness of the cloud of unknowing, you must not even let yourself be distracted by thoughts of God’s blessings and goodness, even though they are holy thoughts that make you feel good.

So let go of every clever, persuasive thought. Put it down and cover it with a thick cloud of forgetting. No matter how sacred, no thought can ever promise to help you in the work of contemplative prayer because only love—not knowledge—can help us reach God. As long as you are a soul living in a mortal body, your intellect, no matter how sharp and spiritually discerning, never sees God perfectly. The mind is always distorted in some way, warping our work; and at its worst, our intellect can lead us to great error.

—The Cloud of Unknowing, Chapter 8

Image: Public Domain

Let’s step back a minute and look at contemplation. Why does it have to be so hard? After all, that profound love stirring again and again in your will requires no straining on your part. These gentle impulses don’t come from you but from the hand of God, the all-powerful, always ready to start this work in anyone who’s done everything possible to get prepared. Then what makes this work so difficult? You must tread down thoughts of every creature that God has ever made and then hold them there, keeping them covered under the cloud of forgetting we discussed earler. This is the hard work. God’s grace will help you roll your sleeves up for it but you still have to do it yourself. On the other hand, God alone sets those loving feelings in motion. So do your part and I can promise you God will do his. He never fails …

Yes, in the beginning it seems demanding and severe, when you’re not yet used to it but as your devotion grows, contemplation ceases being hard and instead becomes very restful and easy. It will hardly seem like work. God will sometimes do it for you then, all by himself, but not every time and never for long; only when he feels like it and in the way he feels like doing it. When that happens, you’ll be happy to leave him alone to do as he wants.

Sometimes God may send out a ray of divine light, piercing this cloud of unknowing between you and him and letting you see some of his ineffable mysteries. You’ll feel on fire with his love then. I can’t describe this experience. It’s beyond words. My foolish, human tongue can’t describe God’s grace. Even if I dared, I would refuse, and that’s that.

—The Cloud of Unknowing, Chapter 26

Image: Public Domain

On a related point, another person might tell you to gather your powers of body, soul and intellect wholly within yourself and worship God there. This is good advice, well put, and if taken in the right way, you can’t find any better. But I don’t recommend this because I worry that such advice might be literally interpreted and mislead someone. My suggestion resists distortion. I only ask that during contemplative prayer steer clear of withdrawing into yourself. I also don’t want you outside, above, behind or on one side or the other of yourself.

‘Where then,’ you ask, ‘will I be? If I take your advice, I’ll end up “nowhere”!’ You’re right. Well said. That’s exactly where I want you because nowhere physically is everywhere spiritually. Make sure that your contemplative work is fully detached from the physical. Remember that when your mind is focused on anything in particular, that’s where you are spiritually, just as certainly as when your physical being is located in a specific place, that’s where your body is. Obviously, during contemplative prayer, your body’s five senses and your soul’s powers will think that you are doing nothing because they find nothing to feed on but don’t let that stop you—keep on working at this ‘nothing’, as long as you are doing it for God’s love. Persevere in contemplation with a renewed longing in your will to have God, remembering that your intellect cannot possess him. For I would rather be nowhere physically, wrestling with this obscure nothing, than be a powerful, rich lord, able to go wherever I want, whenever I want, always amusing myself with every ‘something’ that I own.

So abandon the world’s ‘everywhere’ and ‘something’ in exchange for this infinitely more valuable nowhere and nothing. Don’t be bothered that your intellect is unable to comprehend it. I love it even more for its inscrutability. Its infinite worth makes it incomprehensible. Also, remember that you can more easily feel this nothing than see it. It can be experienced but not grasped. That’s why it seems completely hidden and totally dark to those who’ve only been looking at it for a very short time. Let me clarify ‘dark’ here. When a person experiences this nothing, the soul is blinded by an abundance of spiritual light and not by actual darkness or by an absence of physical light.

So who labels this ‘nothing’? That would be the outer self. Our inner self calls it ‘all’ because experiencing this ‘nothing’ gives us an intuitive sense of all creation, both physical and spiritual, without paying special attention to any one thing.

—The Cloud of Unknowing, Chapter 68

Image: Public Domain

So, work diligently in this nothing, which is nowhere. Put aside your exterior ways of knowing, such as your five senses and their objects of interest because I’m telling you that this contemplative work can’t be accomplished by them.

Your eyes only understand that something is long, wide, small, large, round, square, near, far and colourful. Your ears only comprehend noise or other sounds. Your nose only recognizes a stench or a fragrance. Taste only affords you the ability to know whether something is sour or sweet, salty or fresh, bitter or pleasant. And touch can only teach you whether something is hot or cold, hard or soft or smooth or sharp. But God has none of these dimensions. In fact, nothing spiritual has these characteristics.

So stop trying to work with your body’s senses in any way. Abandon them entirely. Those people who start the inner work of contemplation with the belief that they’re supposed to hear, smell, see, taste or touch spiritual things, inside or outside, are truly misled. They work against nature, taking the wrong approach. Although God has ordained that our body’s senses should teach us about all external and physical things, I mean that in no way do the senses’ various positive activities help us understand spiritual things. Whenever we hear or read about something that our bodies’ superficial senses cannot describe to us in any way, we can be sure that this thing is spiritual and not physical.

We have the same experience in contemplative work when we use our spiritual sense in our struggle to know God himself. Similar limitations apply. It doesn’t matter how much profound wisdom we possess about created spiritual beings; our understanding cannot help us gain knowledge about any uncreated spiritual being, who is God alone. But the failure of understanding can help us. When we reach the end of what we know, that’s where we find God. That’s why St. Dionysius said that the best, most divine knowledge of God is that which is known by not-knowing.

—The Cloud of Unknowing, Chapter 70

Post Notes

- Percy Bysshe Shelley: The Cloud

- John Devitt: Cloud Illusions

- Julian of Norwich: Revelations of Divine Love

- Teresa of Ávila: The Ecstasy of Love

- Hildegard of Bingen: Sibyl of the Rhine

- Philip Gröning: Into Great Silence

- Xavier Beauvois: Of Gods and Men

- Shūsaku Endō: Silence

- T. S. Eliot: A Man Out of Time

- Gospel of Mary Magdalene

- Michael Molinos: The Spiritual Guide