It is a truth universally acknowledged …

Jane Austen House & Chawton House

She was careful that her occupation should not be suspected by servants, or visitors, or any persons beyond her own family party. She wrote upon small sheets of paper which could easily be put away, or covered with a piece of blotting paper. There was, between the front door and the offices, a swing door which creaked when it was opened; but she objected to having this little inconvenience remedied, because it gave her notice when anyone was coming … In that well-occupied female party there must have been many precious hours of silence during which the pen was busy at the little mahogany writing-desk, while Fanny Price, or Emma Woodhouse, or Anne Elliott was growing into beauty and interest. I have no doubt that I, and my sisters and cousins … frequently disturbed this mystic process, without having any idea of the mischief we were doing; certainly we never should have guessed it by any signs of impatience or irritability in the writer.

—J. E. Austen-Leigh, A Memoir of Jane Austen and Other Family Recollections

OUR FIRST SUBJECT in The Culturium’s brand new Writers and Artists Spirituality Series is arguably one of the most beloved English authors ever to have lived—second only to William Shakespeare—whose novels and associated film adaptations continue to grace our literary consciousness.

Born on 16th December 1775 at the village of Steventon in North Hampshire, where her father was the vicar of the small 12th-century church, Steventon Rectory is where Jane would spend the first 25 years of her life.

After unsettling spells in Bath and Southampton, Austen finally moved in 1809 into Chawton Cottage (now the Jane Austen House Museum), her final home with her sister Cassandra, their mother and a friend, Martha Lloyd, where Austen revised and completed her early works Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice and Northanger Abbey, before directing her attention towards composing her later and truly great novels Mansfield Park, Emma and Persuasion (as well as the first 12 chapters of Sanditon before her death).

According to Paula Hollingsworth in her magnificent book, The Spirituality of Jane Austen, it is important to clarify our terminology from the outset, since the word spiritual was not a concept in common usage in Regency England; rather, religious would have been more an appropriate term, specifically Protestant Christian, with its virtues of self-improvement, tolerance and “right” behaviour acting as a person’s moral guide.

Nevertheless, through the lens of our modern perspective, we are able to extract a spiritual sensibility from Austen’s books, if we consider the philosophical and metaphysical components that are an intrinsic aspect of humanity about which she beautifully fashioned her tales: desiring to live in a sacred realm well beyond the confines of materiality; accepting the hand of Providence in the course of one’s unfolding lifespan; and committing to an inner path and the actualization of one’s authentic self.

Indeed, as a devout Anglican born into a clerical family with two of her brothers also becoming clergymen, Jane’s Christianity was foundational to her existence. Subtly weaving her beliefs as a form of “natural law” through the warp and weft of her narratives rather than proselytizing theological debate more in keeping with the Biblical sermons delivered from the pulpit of a chapel, her stories appealed to a broad audience, both religious and secular.

At a precociously young age, Jane read books written specifically for adults, having uncensored access to her father’s library of over five hundred titles. In a time period when it was believed in certain quarters that reading could be detrimental to the development of young ladies’ minds, she defied convention by steeping in the popular fiction of her day, specifically the Gothic and Romantic Sentimental novel, fuelling her imagination to such an extent that she started writing fiction of her own in her teenage years (plays, stories and short fragments, collectively known as her Juvenilia).

At just 20 years of age, Jane began work on her first important novel, setting out to utilize (in her own words) “the greatest powers of her mind” in order to portray a “thorough knowledge of human nature”. In Sense and Sensibility (1811), Jane stresses the importance of developing good character and finding the right balance in life, through emotional awareness and sensitivity to pain and pleasure, tempered by logic and self control; in Pride and Prejudice (1813), she examines moral growth and self-examination through humility and ethical conduct; and in Northanger Abbey (1817, posthumous), she conveys how critical thinking is essential for sound judgement and moral courage.

Then, in Mansfield Park (1814), Jane champions virtues such as kindness, honesty and charity, with her heroine Fanny Price the model of Christian patience; in Emma (1815), she brings her protagonist from insensitivity and self-satisfaction to social responsibility and care for others; and finally in Persuasion (1817, posthumous), through arguably her greatest character of all, Anne Elliot, she investigates the defiance of public influence, standing firm to one’s core beliefs through quiet duty and steadfast love.

Despite clerical characters occurring frequently in all her novels (who can forget Pride and Prejudice‘s satirical critique of clergyman, Mr Collins?), Jane believed faith to be “too serious a subject” for direct treatment. Nevertheless, it is within the pages of Mansfield Park that the role of religion and the church itself are overtly brought to bear, whereby the author uses the upstanding mouths of Fanny Price and Edmund Bertram to discuss the need to rediscover the pastoral profession as a divinely inspired vocation and not just as a means of earning a living wage.

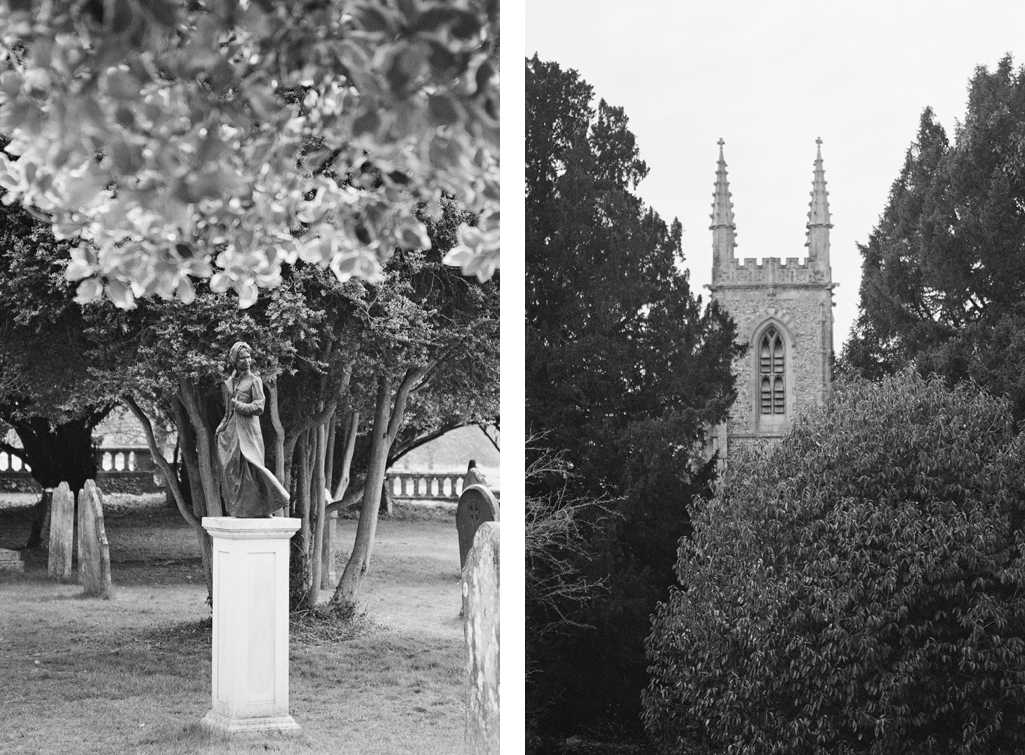

Such fervent ideas sprung from Jane’s own faith and religious practice. Sunday services at St Nicholas Church in Chawton (where there is a beautiful statue of Jane Austen by sculptor Adam Roud) were supplemented by morning and evening family prayers at home. Jane even composed prayers herself, three of which survive today—long and thoughtful petitions to God giving thanks for blessings and interceding “for those ill or travelling, the widows, orphans and prisoners” in language suffused with genuine compassion for her fellow man.

Indeed, it is this very theme of inward reformation, both as an individual and society as a whole in a time period subject to the growing influence of Evangelist ideals, that forms the bedrock of Jane Austen’s world. Through genuine faith, rather than outward religiosity, a silent current of spirituality flows through her immortal words, her plots with their romantic closures pointing to moral vindication for a life lived with integrity, duty and moral conscience.

Jane Austen became seriously ill in 1816, being confined to her bed in April of the following year. On 24th May 1817, Jane left Chawton with Cassandra and moved into lodgings in Winchester, to be near a specialist doctor at the County Hospital. Sadly, her illness worsened considerably and she died early on 18th July 1817. Six days later, she was buried at Winchester Cathedral.

At the time of her death, Jane was just 41 years old, having been poorly for well over a year. It is unclear as to the cause of her death, though Addison’s Disease or Hodgkin’s lymphoma have been cited. Interestingly, when Jane passed away, she was virtually unknown as an author. It was her nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh, whose biography, A Memoir of Jane Austen, did much to revive interest in her work, which has continued unabated ever since.

Cassandra and her mother continued to live at the cottage for the rest of their lives, after which it reverted to the estate of Jane’s brother, Edward Austen (later Knight), who was often in residence at Chawton House (which itself now houses a books and manuscript collection containing over 4,500 rare and early editions of works by women writers in the period 1660–1860, including Jane’s). Over time, Chawton Cottage fell into disrepair until 1948, when a London lawyer, Mr T. Edward Carpenter, established the Jane Austen Memorial Trust to run it as the Jane Austen House Museum, serving as a place of pilgrimage and keeper of Jane’s indelible legacy.

Give us grace, Almighty Father, so to pray, as to deserve to be heard, to address thee with our hearts, as with our lips. Thou art everywhere present, from thee no secret can be hid. May the knowledge of this teach us to fix our thoughts on thee, with reverence and devotion that we pray not in vain.

Look with mercy on the sins we have this day committed and in mercy make us feel them deeply, that our repentance may be sincere & our resolution steadfast of endeavouring against the commission of such in future. Teach us to understand the sinfulness of our own hearts, and bring to our knowledge every fault of temper and every evil habit in which we have indulged to the discomfort of our fellow-creatures, and the danger of our own souls. May we now, and on each return of night, consider how the past day has been spent by us, what have been our prevailing thoughts, words, and actions during it, and how far we can acquit ourselves of evil. Have we thought irreverently of thee, have we disobeyed thy commandments, have we neglected any known duty, or willingly given pain to any human being? Incline us to ask our hearts these questions oh! God, and save us from deceiving ourselves by pride or vanity.

Give us a thankful sense of the blessings in which we live, of the many comforts of our lot; that we may not deserve to lose them by discontent or indifference …

—Jane Austen prayer

Writers & Artists Spirituality Series

Post Notes

- All images: © Paula Marvelly, Jane Austen House Museum, Chawton House, St Nicholas Church

- The Jane Austen Society

- Jane Austen’s House

- Chawton House

- St Nicholas Church

- Adam Roud

- Writers & Artists Spirituality Series

- Mason Currey: Daily Rituals, Women at Work

- T. S. Eliot: A Man Out of Time

- E. M. Forster: The Celestial Omnibus

- Duncan Grant: Berwick Church

- Virginia Woolf: A Room of One’s Own

- Kathleen Raine: The Land Unknown

- Paula Marvelly: The Sacred Feminine Through the Ages

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme