A visionary masterpiece of the beginnings of time

“There are two ways through life … the way of Nature and the way of Grace.

You have to choose which one you’ll follow.”

THERE HAVE ONLY ever been a handful of instances where I have viewed cinematic perfection up on the big screen—Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, Ingmar Bergman’s Persona, Satyajit Ray’s The Apu Trilogy—but now I can add Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life to that elite list, a profoundly surrealistic contemplation of the nature of love and loss and the mysterious workings of time, consciousness and the human condition. Understandably, the film won the illustrious Palme d’Or at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival.

Unless you love … your life will flash by …

Written and directed by Terrence Malick (born 30th November 1943), who read Philosophy at Harvard and Oxford Universities, The Tree of Life is told through Jack O’Brien (played by Sean Penn), a middle-aged corporate executive based in a firm of architects, who is disenchanted with life and looking for some kind of meaning to his existence.

Prompted by the sight of the planting of a tree in front of his office building, Jack then recalls memories from his childhood set in 1950s Waco, Texas, and the relationships he had with his empathetic mother (played by Jessica Chastain) and his disciplinarian father (played by Brad Pitt), as well as the trauma surrounding the death of his brother, R.L., at the age of 19.

Mother. Father. Always you wrestle inside me. Always you will.

Watching The Tree of Life is effectively akin to partaking in a religious experience, and I don’t say that lightly. Poignantly, the film opens with a quote from the Book of Job: “Where were you when I laid the earth’s foundation … while the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?”

A sequence then follows formed by stunning cinematography, with intimate close-ups of sunflowers, waterfalls, the sheen on human skin, transporting us to another world, ethereal and dreamlike, where there is an immediate sense of the loss of self in the face of the sheer beauteousness and wonder of it all.

I didn’t know how to name You then. But I see it was You. Always You were calling me.

In nearly every scene, the sun—either directly or indirectly peeping through foliage, clouds, the surface of the ocean—features as the eternal still point around which the moving images oscillate, turn and spiral, a motif that is carried right through to the end of the film, reminding us of an omnipresent power, forever watching over us, for better or worse.

In the middle and most awe-inspiring sequence of the drama, we are taken on a detour right back to the origins of the universe. In a symphony of Kubrickesque images, including galaxies, deserts and even landscapes populated by dinosaurs, we are all the while beguiled by the operatic accompaniment of Zbigniew Preisner’s Lacrimosa coupled with the whispers of the main protagonists as to the meaning of life. Here is existence, Malick appears to be saying, in all its naked and pristine glory. Behold, gentle viewer, this is nothing less than the Beatific Vision.

Love everyone. Every leaf. Every ray of light.

The remaining section of the film brings us back to earth, or Texas to be more precise, where a series of memories are presented in a nonlinear tableau. This is the hardest part of the movie to follow for there is no discernible narrative to latch onto, no surface meaning to the unfolding, and seemingly nonexistent, plot.

It is only through an act of mental vigilance, by abandoning any hope of understanding where the film is taking us, can we then rest in each and every scene as it arises, thereby allowing ourselves to be overtaken by its metaphysical message, which in turn forces us to consider our inconsequential position in the cosmos.

I will be true to you. Whatever comes.

Despite our insignificance, however, we still have a choice in the way in which we wish to live our allotted lives: the way of Nature, as embodied by Jack’s father—authoritarian, self-centred, worldly; or the way of Grace, embodied by Jack’s mother—tender, self-sacrificing, divine.

The grand finale of The Tree of Life finishes at, what appears to be, the very end of time. Jack finds himself walking behind his younger self in a desert; then, he is transported to the ocean’s shoreline, along with other souls from his childhood past. His mother is then seen, drifting elegantly along the sands, weaving her arms up towards the sunlight. And his brother and father are suddenly here too, assembled within the incorporeal throng. Nature and grace are finally reconciled, it would seem; all is forgiven and peace is restored. It is a majestic ending to a cinematic masterpiece.

Brother. Keep us. Guide us. To the end of time.

Post Notes

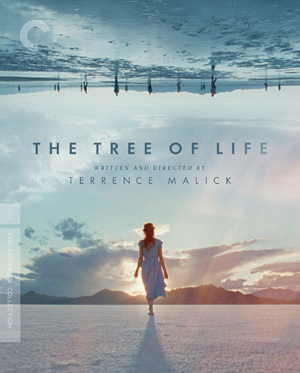

- Feature image: Terrence Malick, The Tree of Life, © Searchlight Pictures

- Andrei Tarkovsky: Cinematic Genius

- Nuri Bilge Ceylan: Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

- Carl Theodor Dreyer: Ordet

- Philip Gröning: Into Great Silence

- Xavier Beauvois: Of Gods and Men

- Pavel Lungin: The Island

- Spiros Stathoulopoulos: Meteora

- Shūsaku Endō: Silence

- Edward A. Burger: Amongst White Clouds

- Kim Ki-duk: Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme