The origin of all things

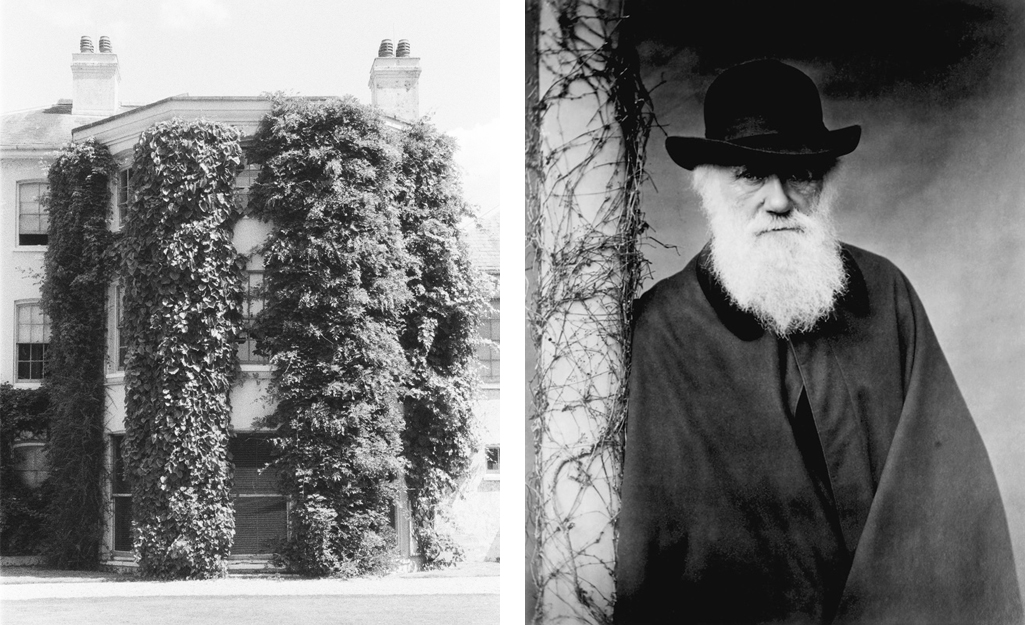

Down House

The affinities of all the beings of the same class have sometimes been represented by a great tree. I believe this simile largely speaks the truth. The green and budding twigs may represent existing species; and those produced during former years may represent the long succession of extinct species. At each period of growth all the growing twigs have tried to branch out on all sides, and to overtop and kill the surrounding twigs and branches, in the same manner as species and groups of species have at all times overmastered other species in the great battle for life … As buds give rise by growth to fresh buds, and these, if vigorous, branch out and overtop on all sides many a feebler branch, so by generation I believe it has been with the great Tree of Life, which fills with its dead and broken branches the crust of the earth, and covers the surface with its ever-branching and beautiful ramifications.

—Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species

CHARLES DARWIN (12th February 1809–19th April 1882), English naturalist and geologist (as well as renowned pigeon-fancier), revolutionized the scientific understanding of life on Earth through his theory of evolution by natural selection, first articulated in On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1859), which established an evolutionary family tree from monkey to man. A figure often associated with scientific materialism despite his holy order training at Christ’s College, Cambridge, Darwin nonetheless possessed a poetic sensibility and a contemplative spirit that emerges in the quieter corners of his writing, where the interdependence and unity of life are celebrated with reverent awe.

Indeed, modern interpretations have drawn parallels between Darwin’s ideas and nondual philosophies. For instance, the concept of “dependent origination” in Buddhism, which posits that all phenomena arise in dependence upon multiple causes and conditions, mirrors the interconnectedness highlighted in his evolutionary hypotheses, though the emergence of Intelligent Design theory and Creationism mean that his concepts remain controversial even to this day.

Down House, which Darwin initially described as “old and ugly” and where he lived for 40 years from 1842 until his death, was the perfect sanctuary offering the very peace and privacy he needed to work on his revolutionary scientific theories, culminating in his groundbreaking seminal text. Currently owned by English Heritage and situated in the rural Kent village of Downe, Darwin lived together with his wife (his first cousin Emma Wedgwood), their ten children, a modest number of domestic staff and an assortment of pets and livestock.

In their decades’ seclusion, Darwin developed his theories further, publishing key works based on his experimental observations carried out at Down House intertwined with his voracious research, including The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication (1868), The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871) and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), in which he famously explores the biological aspects of shared emotional behaviour across species, as well as the phenomenon of blushing, “the most peculiar and most human of all expressions”.

Darwin first established his reputation as an accomplished naturalist when he secured a place on the famed voyage of HMS Beagle, which he admitted “determined my whole career”. Serving as gentleman companion to Captain Robert FitzRoy, the ship set sail on 27th December 1831, taking in Cape Verde Island, Rio de Janeiro, Montevideo, Tierra del Fuego, Cape Horn, the Falkland Islands, Patagonia, the west coast of South America, the Galapagos Islands, Tahiti and New Zealand, with the last leg of the trip focusing on Australia, the Keeling Islands, Mauritius, Cape Town, St Helena and Ascension Island, finally arriving back home on 2nd October 1836.

On his epic journey, Darwin made sketches and wrote copious field notes in a series of small pocketbooks, as well as collected plant, bone and rock specimens, which he packed into barrels and stored in the hold. Over the five years the Beagle circumnavigated the entire planet, Darwin encountered human tribes, flora and fauna never before witnessed by so-called civilized Western man. Upon his return to England, he delivered a paper the following January at the Geological Society about his adventure, which culminated in the publication of The Zoology of the Voyage of HMS Beagle, complete with illustrations, in five parts between 1839 and 1843, the effect of which helped to secure his scientific name and reputation.

I think you will humanize me, & soon teach me there is greater happiness,

than building theories, & accumulating facts in silence and solitude.

—Letter from Charles Darwin to Emma Wedgwood (prior to their wedding, 1839)

Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection posed a profound challenge to the prevailing Christian beliefs of his time, particularly the notion of divine creation as described in the Book of Genesis. By presenting meticulous evidence that all species, including humans, evolved gradually from common ancestors through natural processes, Darwin quietly but radically shifted the framework through which people understood their place in the cosmos. His ideas didn’t outright deny the existence of God but they did suggest that the unfolding of life was governed by impersonal, observable laws rather than supernatural design, prompting a seismic re-evaluation of faith, purpose and the origins of life itself.

As such, his “capital study” at Down House became the centre of his monkish, intellectual world. Preserved and structurally unaltered since Darwin’s day, the Old Study embodies the very essence of a Victorian scientific gentleman’s workplace, with books, correspondence and instruments arranged on a centred rectangular table, with specimens captured in prescription pillboxes and glass-stoppered bottles on a baize-topped drum table next to the window nearby. He always sat on a mahogany-framed horsehair armchair, hunched over a cloth-covered writing board that he balanced across the chair’s arms, which gradually wore away the upholstery beneath.

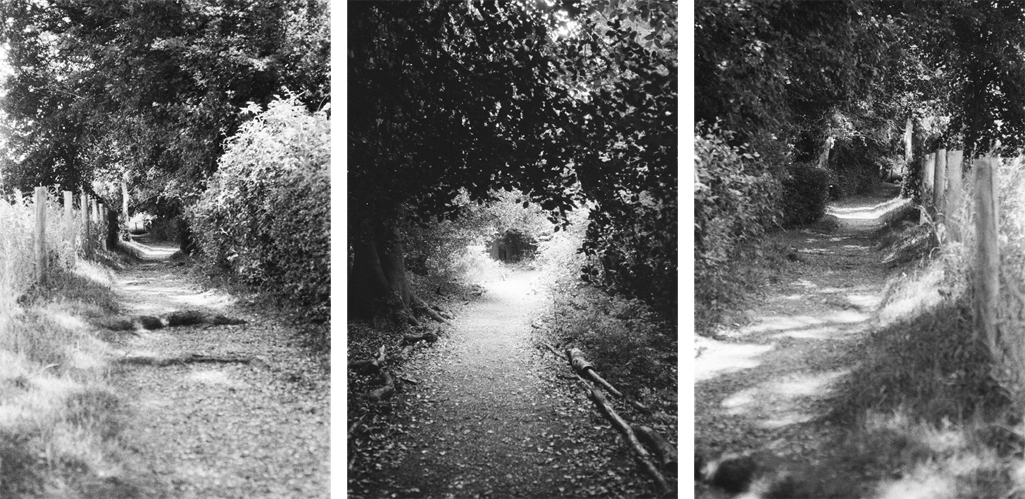

Shortly after his return on the Beagle, Darwin was afflicted with acute stomach problems for the rest of his life, which resulted in frustrating bouts of inactivity—as a result, the left-hand corner of his study was partitioned and curtained off as a makeshift privy. When he was in fairly good health, however, he had a fixed daily routine. Beginning his day with a short walk before breakfast, he then worked in his study until noon, with a break mid-morning to attend to any domestic affairs with Emma and occasional trips to the snuff jar that he kept on a bookcase in the hall. Around midday, he would take a longer walk around a gravel path that circled a small wooded area located at the permitter of his garden, known as the Sandwalk, called as such because it was laid with sand and gravel, making it an ideal track for walking year-round, even in wet weather.

Circumambulating daily this quarter-mile pathway, either alone or with his children, enabled Darwin to use the time for contemplation and reflective thought. Also known as “Darwin’s thinking path” by locals, it was where he worked through many of his ideas, particularly those related to evolution, natural selection and the origins of mankind. He would often walk multiple circuits, placing small stones at the start and kicking one away after each perambulation in order to keep count. His granddaughter, Gwen, described the path as “ominous and solitary” —having sauntered along the Sandwalk myself, I can attest to its eerie quality, which ironically provoked feelings within me to be vigilant of my surroundings, being the instinctual, survival response of a female walking on her own in the woods.

After luncheon at one o’clock, Darwin would then read the newspapers, write letters and go for another walk in the grounds before returning to his study at 4:30pm. An hour or so later, he would rest before dining early and spending the evening quietly in the drawing room playing backgammon with his wife. Of the time he would spend outside, he often would stroll around the lawns, orchard, beehives, kitchen garden and flower beds, as well as tend to the many plants in his beloved greenhouse, used as a laboratory for growing exotic specimens from sproutlings and seeds.

Such was his fascination with botany that he made major contributions to the study of plant anatomy and reproduction (especially orchids and the carnivorous sundew Drosera rotendifolia), together with the processes of circumnutation (the elliptical movement of a plant’s growing tip as it extends and develops), phototropism (the orientation of a plant in response to light), and even the notion that plants could “sleep” when it was dark and be “awake” at the sight of the sun.

In the closing lines of his magnum opus, Darwin meditates upon a “tangled bank” teeming with insects, birds and plants—all shaped by unseen forces and mutual dependence. Far from a cold mechanistic view, his words reveal a profound vision of oneness and a continuous unfolding: a web of life arising from a single, simple wellspring and evolving without hierarchy, separation or control.

Despite declaring of himself in a letter from 1879 that “an agnostic would be the most correct description of my state of mind”, Darwin’s entangled embankment is not merely a metaphor for evolution but a lived expression of unity in diversity, of the infinite’s essence within the finite’s form. Indeed, his words invite us not only to observe the beauty of nature but also to recognize ourselves as a manifestation of the same evolutionary process, the same mystery, the same silent source.

It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us … Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life … that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

—Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species

Writers & Artists Spirituality Series

Post Notes

- All images: © Paula Marvelly, Down House, Greenhouse & Garden,

except Julia Margaret Cameron, Charles Darwin, taken on verandah, Down House, November 1881 - Down House, Home of Charles Darwin, English Heritage

- Writers & Artists Spirituality Series

- Duncan Grant: Berwick Church

- Virginia Woolf: A Room of One’s Own

- T. S. Eliot: A Man Out of Time

- E. M. Forster: The Celestial Omnibus

- Kathleen Raine: The Land Unknown

- Paula Marvelly: The Sacred Feminine Through the Ages

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme